Practical Electronics/Resistors

Resistors are perhaps the most basic electronic component of them all. A resistor opposes the flow of charge (i.e. it resists it). This is very useful for many reasons. For the physical behaviour of resistors, please see the correspondng article in the Electronics Wikibook.

Symbols

The symbol for a resistor is a rectangle, left. The long side should be three times the length of the short side. The contacts are always at the centres of the short sides. This is the modern symbol used in Europe, and in most of the rest of the world, except America and Japan.

The American symbol is a zig-zag shaped kink in the line. This symbol is outmoded and should not be used, for several reasons:

- It reproduces badly at low resolutions and can be confused with other components.

- The symbols for variants are less clear.

- The rectangular symbol is fast replacing it all over the world, and is more widely understood.

The Basics

The amount a resistor resists is measured in "ohms", which has the symbol Ω (a capital omega). This is generally called its value. Resistors used in practical electronics range from one ohm to several million ohms. The normal unit prefixes apply, so we have

| Resistance in Ohms | Unit | Symbol |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ohm | Ω |

| 1,000 | Kiloohm | KΩ |

| 1,000,000 | Megaohm | MΩ |

Often a shorthand is used which means that the Ω symbol, which is usually not easily accessed on a computer, is not needed. The shorthand also eliminates the need for decimal points which are sometimes lost or missed off when documents are copied. The shorthand works by replacing a decimal point with the prefix of the resistance (e.g. K for kilo-ohms) or, for resistances in just ohms, R:

| Standard Notation | Shorthand Notation |

|---|---|

| 1 Ω | 1R |

| 1.2 Ω | 1R2 |

| 1 KΩ | 1K |

| 1.2 KΩ | 1K2 |

This notation is preferred, and will be used in this book. please note that the resistances are still said the same, so the value of a 1K2 resistor is pronounced "one point two kilohms". The shorthand is not used when we are not talking about an individual resistor, for example, when measuring the resistance of a combination of resistors. Then, we express the value in ohms.

Resistors are not made perfect, and so they each have a tolerance. This is the maximum that a resistor can deviate from its specified value. It is expressed in percent, and the standard tolerance is 10%, which is more than adequate for most of our needs.

Preferred Values

To prevent thousands of different values of resistors clogging everything up, resistors only come in specified values. These values are spread across multiples of ten so that each is a constant multiple of the one beneath. The number of divisions per muliple of ten (decade) depends on the tolerance of the resistors. Standard (10%) resistors belong to the E12 series. The values are spread according to the roundend results of the following rule:

These numbers are:

1.0 1.2 1.5 1.8 2.2 2.7 3.3 3.9 4.7 5.6 6.8 8.2

After that, the cycle repeats, but a power of ten higher. Therefore, the first three decades are as follows:

1R 1R2 1R5 1R8 2R2 2R7 3R3 3R9 4R7 5R6 6R8 8R2 10R 12R 15R 18R 22R 27R 33R 39R 47R 56R 68R 82R 100R 120R 150R 180R 220R 270R 330R 390R 470R 560R 680R 820R

This pattern continues right up to the top of the resistor values that are available. For more accurate resistors, there exists an E24 (5%), E96 (1%) and an E192 (0.5%) series. There is also an E6 series for 20% resistors. To se a list of all values in these series, see this appendix.

Colour Codes

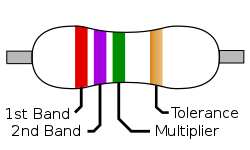

The value and tolerance of a resistor is normally given by a sequence of coloured bands on the resistor body. Normally, there are four bands, three to give the value and one for the tolerance. Occasionally, a fifth band is included to give information about how the resistance changes according to temperature. These are generally found only in military equipment.

| Color | 1st Band | 2nd Band | 3rd Band | 4th Band | 5th Band | Mnemonic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Value | Multiplier | Tolerance | Temp. Coefficient | (for Colour) | |

| Black | 0 | 0 | ×100 | Bad | ||

| Brown | 1 | 1 | ×101 | ±1% | 100 ppm | Boys |

| Red | 2 | 2 | ×102 | ±2% | 50 ppm | Race |

| Orange | 3 | 3 | ×103 | 15 ppm | Our | |

| Yellow | 4 | 4 | ×104 | 25 ppm | Young | |

| Green | 5 | 5 | ×105 | ±0.5% | Girls | |

| Blue | 6 | 6 | ×106 | ±0.25% | But | |

| Violet | 7 | 7 | ×107 | ±0.1% | Violet | |

| Grey | 8 | 8 | ×108 | ±0.05% | Generally | |

| White | 9 | 9 | ×109 | Wins | ||

| Gold | ×0.1 | ±5% | ||||

| Silver | ×0.01 | ±10% (K) | ||||

| None | ±20% (M) |

There is usually a small gap between each value band and a wider gap between the three value bands and the tolerance (and temp. coefficient) bands. These are read last in the code. No resistor colour code ever starts with gold or silver.

The image on the right shows a resistor with a 4-Band colour code.

- The first band is red, so the value starts 2.

- The second band is violets, so the next digit is 7, giving 27.

- The multiplier band is green, so the value is multiplied by 105, giving 2,700,000.

- The tolerance band is gold, so the tolerance is ±5%.

The value of the resistor is therefore 2M7, with a tolerance of 5%.

For an online calculator for resistors with 4, 5, or 6 bands, see [1].

Uses of Resistors

As we saw in a previous chapter, the current flowing in a simple circuit depends only on the voltage and resistance. This means that given a fixed voltage, by changing the resistance, the current can be tuned. The same applies when the voltage is what we want to fix, and the current is constant (or cannot be changed). By altering the resistance, we can set the voltage.

Because they resist flow of charge, resistors are also used to limit the current flowing through sensitive components. For example, an component that has a low resistance but cannot tolerate too much current should be used in series with a resistor, which will limit the current. The exact value of the resistor depends on the specifications of the device being used. A common application like this is when an LED is used. LEDs generally need 2V at 20mA to work properly. Say we have a 9V circuit, we need to lose 7V to operate the LED. Putting this into Ohm's Law, we get:

Therefore, the resistor should be 350R to give the LED 2V at 20mA. However, this is not in the E12 series, so we find the next best, which is 390R. 330R is closer, but may exceed the LED's current capacity, damaging it.

Resistors in Series and Parallel

Series

When resistors are wired in series, the total resistance is the sum of all the individual resistances. For an explanation of this, see this proof. So for the resistor network to the right, the total resistance, Rtot, is:

If n identical resistors are in series, then the total resistance is n times the resistance of those identical resistors. This is useful when you want a simple multiple of the resistance.

When a resistance is added in series with others, the total resistance always increases. The total resistance will therefore be more than the greatest value of resistor present.

Parallel

When resistors are wired in parallel, the reciprocal of the total resistance is the sum of the reciprocals of the individual resistances. For an explanation of this, see this proof. So for the resistor network to the right, the total resistance, Rtot, is:

If n identical resistors are in parallel, then the total resistance is 1/n the resistance of those identical resistors. This is useful when you want a simple fraction of the resistance.

When a resistance is added in parallel with others, the total resistance always decreases. The total resistance will therefore be less than the smallest value of resistor present.

Series and Parallel

Resistors can also be combined in a combination of series and parallel. To calculate the total resistance in these cases, simply break it into smaller parts that are basic series/parallel combinations and treat each one as one resistor. Consider the arrangement to the right. This is made up of two resistors in parallel, in series with another resistor.

The resistance of the two in parallel is:

When combined in series with the other resistance,