Organic Chemistry/Foundational concepts of organic chemistry/Atomic structure

< History | Electronegativity >

|

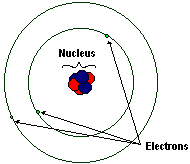

| A simple model of a lithium atom. Not to scale! |

Atomic Structure

Atoms are made up of a nucleus and electrons that orbit the nucleus. The nucleus consists of protons and neutrons. An atom in its natural, uncharged state has the same number of electrons as protons.

The nucleus

The nucleus is made up of protons, which are positively charged, and neutrons, which have no charge. Neutrons and protons have about the same mass, and together account for most of the mass of the atom. Each of these particles is made up of even smaller particles, though the existence of these particles does not come into play at the energies and time spans in which most chemical reactions occur. The ratio of protons to neutrons is fairly critical, and any departure from the optimum range will lead to nuclear instability and thus radioactivity.

Electrons

The electrons are negatively charged particles. The mass of an electron is about 2000 times smaller than that of a proton or neutron at 0.00055 amu. Electrons circle so fast that it cannot be determined where electrons are at any point in time, rather, we talk about the probability of finding an electron at a point in space relative to a nucleus at any point in time. The image depicts the old Bohr model of the atom, in which the electrons inhabit discrete "orbitals" around the nucleus much like planets orbit the sun. This model is outdated. Current models of the atomic structure hold that electrons occupy fuzzy clouds around the nucleus of specific shapes, some spherical, some dumbbell shaped, some with even more complex shapes. Even though the simpler Bohr model of atomic structure has been superseded, we still refer to these electron clouds as "orbitals". The number of electrons and the nature of the orbitals they occupy basically determines the chemical properties and reactivity of all atoms and molecules.

Shells and Orbitals

Electron orbitals

Electrons orbit atoms in clouds of distinct shapes and sizes. The electron clouds are layered one inside the other into units called shells (think nested Russian dolls), with the electrons occupying the simplest orbitals in the innermost shell having the lowest energy state and the electrons in the most complex orbitals in the outermost shell having the highest energy state. The higher the energy state, the more energy the electron has, just like a rock at the top of a hill has more potential energy than a rock at the bottom of a valley. The main reason why electrons exist in higher energy orbitals is because only two electrons can exist in any orbital. So electrons fill up orbitals, always taking the lowest energy orbitals available. An electron can also be pushed to a higher energy orbital, for example by a photon. Typically this is not a stable state and after a while the electron descends to lower energy states by emitting a photon spontaneously. These concepts will be important in understanding later concepts like optical activity of chiral compounds as well as many interesting phenomena outside the realm of organic chemistry (for example, how lasers work).

Wave nature of electrons

The result of this observation is that electrons are not just in simple orbit around the nucleus as we imagine the moon to circle the earth, but instead occupy space as if they were a wave on the surface of a sphere.

If you jump a jumprope you could imagine that the wave in the rope is in its fundamental frequency. The high and low points fall right in the middle, and the places where the rope doesn't move much (the nodes) occur only at the two ends. If you shake the rope fast enough in a rythmic way, using more energy than you would just jumping rope, you might be able to make the rope vibrate with a wavelength shorter than the fundamental. You then might see that the rope has more than one place along its length where it vibrates from its highest spot to its lowest spot. Furthermore, you'll see that there are one or more places (or nodes) along its length where the rope seems to move very little, if at all.

Or consider stringed musical instruments. The sound made by these instruments comes from the different ways, or modes the strings can vibrate. We can refer to these different patterns or modes of vibrations as linear harmonics. Going from there, we can recognize that a drum makes sound by vibrations that occur across the 2-dimensional surface of the drumhead. Extending this now into three dimensions, we think of the electron as vibrating across a 3-dimensional sphere, and the patterns or modes of vibration are referred to as spherical harmonics. The mathematical analysis of spherical harmonics were worked out by the French mathematician Legendre long before anyone started to think about the shapes of electron orbitals. The algebraic expressions he developed, known as Legendre polynomials, describe the three dimension shapes of electron orbitals in much the same way that the expression x2+y2 = z2 describes a circle (or, for that matter, a drumhead). Many organic chemists need never actually work with these equations, but it helps to understand where the pictures we use to think about the shapes of these orbitals come from.

Electron shells

Each different shell is subdivided into one or more orbitals, which also have different energy levels, although the energy difference between orbitals is less than the energy difference between shells.

Longer wavelengths have less energy; the s orbital has the longest wavelength allowed for an electron orbiting a nucleus and this orbital is observed to have the lowest energy.

Each orbital has a characteristic shape which shows where electrons most often exist. The orbitals are named using letters of the alphabet. In order of increasing energy the orbitals are: s, p, d, and f orbitals.

As one progresses up through the shells (represented by the principal quantum number n) more types of orbitals become possible. The shells are designated by numbers. So the 2s orbital refers to the s orbital in the second shell.

S orbital

The s orbital is the orbital lowest in energy and is spherical in shape. Electrons in this orbital are in their fundamental frequency. This orbital can hold a maximum of two electrons.

P orbital

The next lowest-energy orbital is the p orbital. Its shape is often described as like that of a dumbbell. There are three p-orbitals each oriented along one of the 3-dimensional coordinates x, y or z. Each of these three "p" orbitals can hold a maximum of two electrons.

These three different p orbitals can be referred to as the px, py, and pz.

The s and p orbitals are important for understanding most of organic chemistry as these are the orbitals that are occupied by the type of atoms that are most common in organic compounds.

D and F orbitals

There are also D and F orbitals. D orbitals are present in transition metals. Sulfur and phosphorus have empty D orbitals. Compounds involving atoms with D orbitals do come into play, but are rarely part of an organic molecule. F are present in the elements of the lanthanide and actinide series. Lanthanides and actinides are mostly irrelevant to organic chemistry.

Filling electron shells

When an atom or ion receives electrons into its orbitals, the orbitals and shells fill up in a particular manner.

There are three principles that govern this process:

- the Pauli exclusion principle,

- the Aufbau (build-up) principle, and

- Hund's rule.

Pauli exclusion principle

No more than one electron can have all four quantum numbers the same. What this translates to in terms of our pictures of orbitals is that each orbital can only hold two electrons, one "spin up" and one "spin down".

The Pauli exclusion principle is a quantum mechanical principle formulated by Wolfgang Pauli in 1925, which states that no two identical fermions may occupy the same quantum state simultaneously. It is one of the most important principles in physics, primarily because the three types of particles from which ordinary matter is made—electrons, protons, and neutrons—are all subject to it. The Pauli exclusion principle underlies many of the characteristic properties of matter, from the large-scale stability of matter to the existence of the periodic table of the elements.

Pauli exclusion principle follows mathematically from definition of wave function for a system of identical particles - it can be either symmetric or antisymmetric (depending on particles' spin).

Particles with antisymmetric wave function are called fermions - they have to obey the Pauli exclusion principle. Apart from the familiar electron, proton and neutron, these include the neutrinos, the quarks (from which protons and neutrons are made), as well as some atoms like helium-3. All fermions possess "half-integer spin", meaning that they possess an intrinsic angular momentum whose value is given by Dirac's constant (Planck's constant divided by 2π) times a half-integer (1/2, 3/2, 5/2, etc.). In the theory of quantum mechanics, fermions are described by "antisymmetric states", which are explained in greater detail in the article on identical particles.

Particles with integer spin have symmetric wave function and are called bosons, in contrast to fermions they share same quantum states. Examples of bosons include the photon and the W and Z bosons.

Build-up principle

According to the principle, electrons fill orbitals starting at the lowest available energy states before filling higher states (e.g. 1s before 2s).

You may consider an atom as being "built up" from a naked nucleus by gradually adding to it one electron after another, until all the electrons it will hold have been added. Much as one fills up a container with liquid from the bottom up, so also are the orbitals of an atom filled from the lowest energy orbitals to the highest energy orbitals.

However, the three p orbitals of a given shell all occur at the same energy level. So, how are they filled up? Is one of them filled full with the two electrons it can hold first, or do each of the three orbitals receive one electron apiece before any single orbital is double occupied? As it turns out, the latter situation occurs.

Hund's rule

This states that filled and half-filled shells tend to have additional stability. In some instances, then, for example, the 4s orbitals will be filled before the 3d orbitals.

This rule is applicable only for those elements that have d electrons, and so is less important in organic chemistry (though it is important in organometallic chemistry).

From WP: Hund's rule of maximum multiplicity, often simply referred to as Hund's rule, is a principle of atomic chemistry which states that a greater total spin state usually makes the resulting atom more stable, most commonly manifested in a lower energy state, because it forces the unpaired electrons to reside in different spatial orbitals. A commonly given reason for the increased stability of high multiplicity states is that the different occupied spatial orbitals create a larger average distance between electrons, reducing electron-electron repulsion energy. In reality, it has been shown that the actual reason behind the increased stability is a decrease in the screening of electron-nuclear attractions. Total spin state is calculated as the total number of unpaired electrons + 1, or twice the total spin + 1 written as 2s+1.

Octet rule

The octet rule states that atoms tend to prefer to have eight electrons in their valence shell, so will tend to combine in such a way that each atom can have eight electrons in its valence shell, similar to the electronic configuration of a noble gas. In simple terms, molecules are more stable when the outer shells of their constituent atoms are empty, full, or have eight electrons in the outer shell.

The main exception to the rule is hydrogen, which is at lowest energy when it has two electrons in its valence shell.

Other notable exceptions are aluminum and boron, which can function well with six valence electrons; and some atoms beyond group three on the periodic table that can have over eight electrons, such as sulfur. Additionally, some noble gasses can form compounds when expanding their valence shell.

The other tendency of atoms with regard to their electrons is to maintain a neutral charge. Only the noble gasses have zero charge with filled valence octets. All of the other elements have a charge when they have eight electrons all to themselves. The result of these two guiding principals is the explanation for much of the reactivity and bonding that is observed within atoms; atoms seeking to share electrons in a way that minimizes charge while fulfilling an octet in the valence shell.

Molecular orbitals

Carbon in an SP3 electron formation, like methane

In organic chemistry we look at the hybridization of electron orbitals into something called molecular orbitals.

A tetrahedron

The s and p orbitals in a carbon atom combine into four hybridized orbitals that repel each other in a shape much like that of four balloons tied together. Carbon takes this tetrahedral shape because it only has six electrons which fill the s but only two of the p orbitals.

When all the s and p orbitals are entirely full the atom's electron clouds form a shape called an octahedral, which is similar to a 3-dimensional diamond in that it is formed by two square pyramids whose bases are placed against each other.

Hybridization

Hybridization refers to the combining of the orbitals of two or more covalently bonded atoms. Depending on how many free electrons a given atom has and how many bonds it is forming, the electrons in the s and the p orbitals will combine in certain manners to form the bonds.

It is easy to determine the hybridization of an atom given a Lewis structure. First, you count the number of pairs of free electrons and the number of sigma bonds (single bonds). Do not count double bonds, since they do not affect the hybridization of the atom. Once the total of these two is determined, the hybridization pattern is as follows:

Sigma Bonds + Electron Pairs Hybridization

2 sp

3 sp2

4 sp3

The pattern here is the same as that for the electron orbitals, which serves as a memory guide.

<< Foundational concepts | < History | Atomic Structure | Electronegativity > | Alkanes >>