Discrete mathematics/Functions and relations

In this article, we will take a closer look at the previous concept of the function more closely than you would have previously had experience with.

We will also examine the concept of the relation, and properties these can have.

INTRODUCTION:

Functions

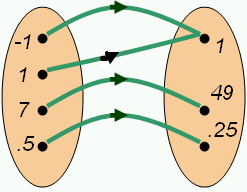

A function is a relationship between two different sets of numbers. We call this also a mapping. A function essentially maps a number in one set to another number in another set.

We write functions as:

- Notice that when we talk about a function it is important to keep in mind that a function maps values to one and only one value only. Two values in one set could map to one value, but one value must never map to two values: that is called a relation, not a function.

|

For example, if we define

then we have

PROBLEM SET: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10.

and so on. f, in this instance, maps numbers to their squares.

Range, image, codomain

If D is a set, we can say

which forms a new set, called the range of f. D is called the domain of f, and represents all values that f takes.

In general, the range of f is usually a subset of a larger set. This set is known as the codomain of a function. For example, with the function f(x)=cos x, the range of f is [-1,1], but the codomain is the set of real numbers.

Notations

When we have a function f, with domain D and range R, we write:

If we say that, for instance, x is mapped to x2, we also can add

Notice that we can have a function that maps a point (x,y) to a real number, or some other function of two variables -- we have a set of ordered pairs as the domain. Recall from set theory that this is defined by the Cartesian product - if we wish to represent a set of all real-valued ordered pairs we can take the Cartesian product of the real numbers with itself to obtain

- .

When we have a set of n-tuples as part of the domain, we say that the function is n-ary (for numbers n=1,2 we say unary, and binary respectively).

Other function notation

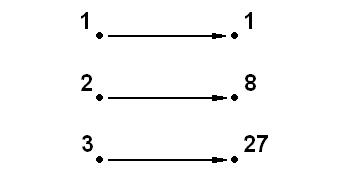

Functions can be written as above, but we can also write them in two other ways. One way is to useItalic text an arrow diagram to represent the mappings between each element. We write the elements from the domain on one side, and the elements from the range on the other, and we draw arrows to show that an element from the domain is mapped to the range.

For example, for the function f(x)=x3, the arrow diagram for the domain {1,2,3} would be:

Another way is to use set notation. If f(x)=y, we can write the function in terms of its mappings. This idea is best to show in an example.

Let us take the domain D={1,2,3}, and f(x)=x2. Then, the range of f will be R={f(1),f(2),f(3)}={1,4,9}. Taking the Cartesian product of D and R we obtain F={(1,1),(2,4),(3,9)}.

So using set notation, a function can be expressed as the Cartesian product of its domain and range.

f(x)

This function is called f, and it takes a variable x. We substitute some value for x to get the second value, which is what the function maps x to.

INTRODUCTION:

Relations

In the above section dealing with functions and their properties, we noted the important property that all functions must have, namely that if a function does map a value from its domain to its codomain, it must map this value to only one value in the codomain.

Writing in set notation, if a is some fixed value:

- |{f(x)|x=a}|=1

However, when we consider the relation, we relax this constriction, and so a relation may map one value to more than one other value. In general, a relation is any subset of the Cartesian product of its domain and codomain.

All functions, then, can be considered as relations also.

Notations

When we have the property that one value is related to another, we call this relation a binary relation and we write it as

- x R y

where R is the relation.

For arrow diagrams and set notations, remember for relations we do not have the restriction that functions do and we can draw an arrow to represent the mappings, and for a set diagram, we need only write all the ordered pairs that the relation does take: again, by example

- f = {(0,0),(1,1),(1,-1),(2,2),(2,-2)}

is a relation and not a function, since both 1 and 2 are mapped to two values, 1 and -1, and 2 and -2 respectively.

Some simple examples

Let us examine some simple relations.

Say f is defined by

- {(0,0),(1,1),(2,2),(3,3),(1,2),(2,3),(3,1),(2,1),(3,2),(1,3)}

This is a relation (not a function) since we can observe that 1 maps to 2 and 3, for instance.

Less-than, "<", is a relation also. Many numbers can be less than some other fixed number, so it cannot be a function.

Properties

When we are looking at relations, we can observe some special properties different relations can have.

Reflexive

A relation is reflexive if, we observe that for all values a:

- a R a

In other words, all values are related to themselves

The relation of equality, "=" is reflexive. Observe that for, say, all numbers a (the domain is R):

- a = a

So "=" is reflexive.

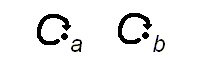

In a reflexive relation, we have arrows for all values in the domain pointing back to themselves:

Symmetric

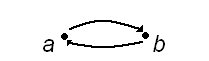

A relation is symmetric if, we observe that for all values a and b:

- a R b implies b R a

The relation of equality again is symmetric. If x=y, we can also write that y=x also.

In a symmetric relation, for each arrow we have also an opposite arrow, ie. there is either no arrow between x and y, or an arrow points from x to y and an arrow back from y to x:

Transitive

A relation is transitive if for all values a, b, c:

- a R b and b R c implies a R c

The relation greater-than ">" is transitive. If x > y, and y > z, then it is true that x > z. This becomes clearer when we write down what is happening into words. x is greater than y and y is greater than z. So x is greater than both y and z.

In the arrow diagram, every arrow between two values a and b, and b and c, has an arrow going straight from a to c.

Antisymmetric

A relation is antisymmetric if, we observe that for all values a and b:

- a R b and b R a implies that a=b

Notice that antisymmetric is not the same as "not symmetric".

Take the relation greater than or equals to, "≥" If x ≥ y, and y ≥ x, then y must be equal to x.

Trichotomy

A relation satisfies trichotomy if we observe that for all values a and b it holds true that: aRb or bRa

Problem set

Given the above information, determine which relations are reflexive, transitive, symmetric, or antisymmetric on the following - there may be more than one characteristic. (Answers follow to even numbered questions.) x R y if

- x = y

- x < y

- x2 = y2

- x ≤ y

Answers

1.Symmetric

- 2. Transitive.

3.Symmetric

- 4. Reflexive, antisymmetric, transitive.

Equivalence relations

We have seen that certain common relations such as "=", and congruence (which we will deal with in the next section) obey some of these rules above. The relations we will deal with are very important in discrete mathematics, and are known as equivalence relations. They essentially assert some kind of equality notion, or equivalence, hence the name.

Characteristics of equivalence relations

For a relation R to be an equivalence relation, it must have the following properties, viz. R must be:

- reflexive

- symmetric

- transitive

(A helpful mnemonic, R-S-T)

In the previous problem set you have shown equality, "=", to be reflexive, symmetric, and transitive. So "=" is an equivalence relation.

We denote an equivalence relation, in general, by .

Example proof

Say we are asked to prove that "=" is an equivalence relation. We then proceed to prove each property above in turn (Often, the proof of transitivity is the hardest).

Reflexive

Clearly, it is true that a = a for all values a. So = is reflexive.

Symmetric

If a = b, it is also true that b = a. So = is symmetric

Transitive

If a = b and b = c, this says that a is the same as b which in turn is the same as c. So a is then the same as c, so a = c, and thus = is transitive.

Thus = is an equivalence relation.

Partitions and equivalence classes

It is true that when we are dealing with relations, we may find that many values are related to one fixed value.

For example, when we look at the quality of congruence, which is that given some number a, a number congruent to a is one that has the same remainder or modulus when divided by some number n, as a, which we write

- a ≡ b (mod n)

and is the same as writing

- a = b+kn for some integer k.

(We will look into congruences in further detail later, but a simple examination or understanding of this idea will be interesting in its application to equivalence relations)

For example, 2 ≡ 0 (mod 2), since the remainder on dividing 2 by 2 is in fact 0, as is the remainder on dividing 0 by 2.

We can show that congruence is an equivalence relation (This is left as an exercise, below Hint use the equivalent form of congruence as described above).

However, what is more interesting is that we can group all numbers that are equivalent to each other.

With the relation congruence modulo 2 (which is using n=2, as above), or more formally:

- x ~ y if and only if x ≡ y (mod 2)

we can group all numbers that are equivalent to each other. Observe:

This first equation above tells us all the even numbers are equivalent to each other under ~, and all the odd numbers under ~.

We can write this in set notation. However, we have a special notation. We write:

- [0]={0,2,4,...}

- [1]={1,3,5,...}

and we call these two sets equivalence classes.

All elements in an equivalence class by definition are equivalent to each other, and thus note that we do not need to include [2], since 2 ~ 0.

We call the act of doing this 'grouping' with respect to some equivalence relation partitioning (or further and explicitly partitioning a set S into equivalence classes under a relation ~). Above, we have partitioned Z into equivalence clases [0] and [1], under the relation of congruence modulo 2.

Problem set

Given the above, answer the following questions on equivalence relations (Answers follow to even numbered questions)

- Prove that congruence is an equivalence relation as before (See hint above).

- Partition {x | 1 ≤ x ≤ 9} into equivalence classes under the equivalence relation

Answers

2. [0]={0,6}, [1]={1,7}, [2]={2,8}, [3]={3,9}, [4]={4}, [5]={5}

Partial orders

We also see that "≥" and "≤" obey some of the rules above. Are these special kinds of relations too, like equivalence relations? Yes, in fact, these relations are specific examples of another special kind of relation which we will describe in this section: the partial order.

As the name suggests, this relation gives some kind of ordering to numbers.

Characteristics of partial orders

For a relation R to be a partial order, it must have the following three properties, viz R must be:

- reflexive

- antisymmetric

- transitive

(A helpful mnemonic, R-A-T)

We denote a partial order, in general, by .

Example proof

Say we are asked to prove that "≤" is a partial order. We then proceed to prove each property above in turn (Often, the proof of transitivity is the hardest).

Reflexive

Clearly, it is true that a ≤ a for all values a. So ≤ is reflexive.

Antisymmetric

If a ≤ b, and b ≤ a, then a must be equal to b. So ≤ is antisymmetric

Transitive

If a ≤ b and b ≤ c, this says that a is less than b and c. So a is less than c, so a ≤ c, and thus ≤ is transitive.

Thus ≤ is a partial order.

Problem set

Given the above on partial orders, answer the following questions 1. Prove that divisibility, |, is a partial order (a | b means that a is a factor of b, ie., on dividing b by a, no remainder results). 2. Prove the following set is a partial order:

- (a, b) <= (c, d) implies ab≤cd for a,b,c,d integers ranging from 0 to 5.

Answers

2. Simple proof; Formalization of the proof is an optional exercise.

- Reflexivity: (a, b) <= (a, b) since ab=ab.

- Antisymmetric: (a, b) <= (c, d) and (c, d) <= (a, b) since ab≤cd and cd≤ab imply ab=cd.

- Transitive: (a, b) <= (c, d) and (c, d) <= (e, f) implies (a, b) <= (e, f) since ab≤cd≤ef and thus ab≤ef

Posets

A partial order imparts some kind of "ordering" amongst elements of a set. For example, we only know that 2 ≥ 1 because of the partial ordering ≥.

We call a set A, ordered under a general partial ordering File:Preceq.png, a partially ordered set, or simply just poset, and write it (A, <=).

Terminology

There is some specific terminology that will help us understand and visualize the partial orders.

When we have a partial order File:Preceq.png, such that a<=b, we write  to say that a <= but a ≠ b. We say in this instance that a precedes b, or a is a predecessor of b.

to say that a <= but a ≠ b. We say in this instance that a precedes b, or a is a predecessor of b.

If (A, <=) is a poset, we say that a is an immediate predecessor of b (or a immediately preceds b) if there is no x in A such that a  x

x  b.

b.

If we have the same poset, and we also have a and b in A, then we say a and b are comparable if a <= b and b <= a. Otherwise they are incomparable.

Hasse diagrams

Hasse diagrams are special diagrams that enable us to visualize the structure of a partial ordering. They use some of the concepts in the previous section to draw the diagram.

A Hasse diagram of the poset (A, File:Preceq.png) is constructed by

- placing elements of A as points

- if a and b ∈ A, and a is an immediate predecessor of b, we draw a line from a to b

- if a

b, put the point for a lower than the point for b

b, put the point for a lower than the point for b - not drawing loops from a to a (this is assumed in a partial order because of reflexivity)

Operations on Relations

There are some useful operations one can perform on relations, which allow to express some of the above mentioned properties more briefly.

Inversion

Let R be a relation, then its inversion, R-1 is defined by

R-1 := {(a,b) | (b,a) in R}.

Concatenation

Let R be a relation between the sets A and B, S be a relation between B and C. We can concatenate these relations by defining

R • S := {(a,c) | (a,b) in R and (b,c) in S for some b out of B}

Diagonal of a Set

Let A be a set, then we define the diagonal (D) of A by

D(A) := {(a,a) | a in A}

Shorter Notations

Using above definitions, one can say (lets assume R is a relation between A and B):

R is transitive if and only if R • R is a subset of R.

R is reflexive if and only if D(A) is a subset of R.

R is symmetric if R-1 is a subset of R.

R is antisymmetric if and only if the intersection of D(A) and R is D(A).

R is asymmetric if and only if the intersection of D(A) and R is empty.

R is a function if and only if R-1 • R is a subset of D(B).

In this case it is a function A → B. Let's assume R meets the condition of being a function, then

R is injective if R • R-1 if a subset of D(A).

R is surjective if {b | (a,b) in R} = B.

This is incomplete and a draft, additional information is to be added

Previous topic:[[../Functions and relations/]]|Contents:Discrete mathematics|Next topic:[[../Number theory/]]