LaTeX/Formatting

The term formatting is rather broad, but in this case it needs to be as this section will guide you through the various text, paragraph and page formatting techniques. Formatting tends to refer to most things to do with appearance, it makes the list of possible topics quite eclectic: text style, font, size; paragraph alignment, interline spacing, indents; special paragraph types; list structures; footnotes, margin notes, etc.

A lot of the formatting techniques are required to differentiate certain elements from the rest of the text. It is often necessary to add emphasis to key words or phrases. A numbered or bulleted list is also commonly used as a clear and concise way of communicating an important issue. Footnotes are useful for providing extra information or clarification without interrupting the main flow of text. So, for these reasons, formatting is very important. However, it is also very easy to abuse, and a document that has been over-done can look and read worse than one with none at all.

Text formatting

Hyphenation

LaTeX hyphenates words whenever necessary. If the hyphenation algorithm does not find the correct hyphenation points, you can remedy the situation by using the following commands to tell TeX about the exception. The command

\hyphenation{word list}

causes the words listed in the argument to be hyphenated only at the points marked by “-”. The argument of the command should only contain words built from normal letters, or rather signs that are considered to be normal letters by LaTeX. The hyphenation hints are stored for the language that is active when the hyphenation command occurs. This means that if you place a hyphenation command into the preamble of your document it will influence the English language hyphenation. If you place the command after the \begin{document} and you are using some package for national language support like babel, then the hyphenation hints will be active in the language activated through babel. The example below will allow “hyphenation” to be hyphenated as well as “Hyphenation”, and it prevents “FORTRAN”, “Fortran” and “fortran” from being hyphenated at all. No special characters or symbols are allowed in the argument. Example:

\hyphenation{FORTRAN Hy-phen-a-tion}

The command \- inserts a discretionary hyphen into a word. This also becomes the only point hyphenation is allowed in this word. This command is especially useful for words containing special characters (e.g., accented characters), because LaTeX does not automatically hyphenate words containing special characters.

\begin{minipage}{2in}

I think this is: su\-per\-cal\-%

i\-frag\-i\-lis\-tic\-ex\-pi\-%

al\-i\-do\-cious

\end{minipage}

|

Several words can be kept together on one line with the command

\mbox{text}

It causes its argument to be kept together under all circumstances. Example:

My phone number will change soon. It will be \mbox{0116 291 2319}.

\fbox is similar to \mbox, but in addition there will be a visible box drawn around the content.

Quotes

Latex treats left and right quotes as different entities. For single quotes, ` (on British and American keyboards, this symbol is found on the key adjacent to the number 1) gives a left quote mark, and ' is the right. For double quotes, simply double the symbols, and Latex will interpret them accordingly. (Although, you can use the " for right double quotes if you wish).

| To `quote' in Latex | |

| To ``quote'' in Latex | |

| To ``quote" in Latex | |

| ``Please press the ‘x' key. | “Please press the ‘x’ key.” |

The right quote is also used for apostrophe in Latex without trouble.

Accents

It does not take long before you need to use an accented character within your document. Personally, I find it tends to be names of researchers whom I wish to cite which contain accents. It's easy to apply, although not all are easy to remember!:

To place an accent on top of an i or a j, its dot has to be removed. This is accomplished by typing \i and \j. If you have to write all your document in a foreign language and you have to use particular accents several times, then using the right configuration you can write those characters directly in your document. For more information, see the Internationalization.

The Space Between Words

To get a straight right margin in the output, LaTeX inserts varying amounts of space between the words. It inserts slightly more space at the end of a sentence, as this makes the text more readable. LaTeX assumes that sentences end with periods, question marks or exclamation marks. If a period follows an uppercase letter, this is not taken as a sentence ending, since periods after uppercase letters normally occur in abbreviations.

Any exception from these assumptions has to be specified by the author. A backslash in front of a space generates a space that will not be enlarged. A tilde ‘~’ character generates a space that cannot be enlarged and additionally prohibits a line break. The command \@ in front of a period specifies that this period terminates a sentence even when it follows an uppercase letter.

The additional space after periods can be disabled with the command

\frenchspacing

which tells LaTeX not to insert more space after a period than after ordinary character. This is very common in non-English languages, except bibliographies. If you use \frenchspacing, the command \@ is not necessary.

Some very long words, numbers or URLs may not be hyphenated properly and move far beyond side margin. One solution for this problem is to use sloppypar environment, which tells LaTeX to adjust word spacing less strictly. As result, some spaces between words may be a bit too large, but long words will be placed properly.

Ligatures

Some letter combinations are typeset not just by setting the different letters one after the other, but by actually using special symbols (like "ff"), called ligatures.

Ligatures can be prohibited by inserting {} between the two letters in question. This might be necessary with words built from two words. Here is an example:

\Large Not shelfful\\

but shelf{}ful

|

|

Slash marks

The normal typesetting of the / character in LaTeX does not allow following characters to be "broken" on to new lines, which often create "overfull" errors in output (where letters push off the margin). Words that use slash marks, such as "input/output" should be typeset as "input\slash output", which allow the line to "break" after the slash mark (if needed). The use of the / character in LaTeX should be restricted to units, such as "mm/year", which should not be broken over multiple lines.

Emphasizing Text

In order to add some emphasis to a word or phrase, the simplest way is to use the \emph{text} command. That's it! See, dead easy.

I want to \emph{emphasize} a word.

|

Font Styles and size

I will really only scratch the surface about this particular field. This section is not about how to get your text in Verdana size 12pt! There are three main font families: roman (such as Times), sans serif (eg Arial) and monospace (eg Courier). You can also specify styles such as italic and bold. The following table lists the commands you will need to access the typical font styles:

You may have noticed the absence of underline. This functionality has to be added with the ulem package. Stick \usepackage{ulem} in your preamble. By default, this overrides the \emph command with the underline rather than the italic style. It is unlikely that you wish this to be the desired effect, so it is better to stop ulem taking over \emph and simply call the underline command as and when it is needed.

- To disable

ulem, add\normalemstraight after the document environment begins. - To underline, use

\uline{...}. - To add a wavy underline, use

\uwave{...}. - And for a strike-out

\sout{...}.

Finally, there is the issue of size. This too is very easy, simply follow the commands on this table:

|

Note that the font size definitions are set by the document style. Depending on the document style the actual font size may differ from that listed above. And not every document style has unique sizes for all 10 size commands.

Even if you can easily change the output of your fonts using those commands, you're better off not using explicit commands like this, because they work in opposition to the basic idea of LaTeX, which is to separate the logical and visual markup of your document. This means that if you use the same font changing command in several places in order to typeset a special kind of information, you should use \newcommand to define a "logical wrapper command" for the font changing command.

\newcommand{\oops}[1]{\textbf{#1}}

Do not \oops{enter} this room,

it’s occupied by \oops{machines}

of unknown origin and purpose.

|

Do not enter this room, it’s occupied by machines of unknown origin and purpose. |

This approach has the advantage that you can decide at some later stage that you want to use some visual representation of danger other than \textbf, without having to wade through your document, identifying all the occurrences of \textbf and then figuring out for each one whether it was used for pointing out danger or for some other reason.

Symbols and special characters

Dashes and Hyphens

LaTeX knows four kinds of dashes: a hyphen (-), en dash (–), em dash (—), or a minus sign (−). You can access three of them with different numbers of consecutive dashes. The fourth sign is actually not a dash at all—it is the mathematical minus sign:

Hyphen: daughter-in-law, X-rated\\

En dash: pages 13--67\\

Em dash: yes---or no? \\

Minus sign: $0$, $1$ and $-1$

|

|

The names for these dashes are: ‘-’(-) hyphen , ‘--’(–) en-dash , ‘---’(—) em-dash and ‘’(−) minus sign. They have different purposes:

Euro € currency symbol

When writing about money these days, you need the Euro symbol. You have several choices. If the fonts you are using have a euro symbol and you want to use that one, first you have to load the textcomp package in the preamble:

\usepackage{textcomp}

then you can insert the euro symbol with the command \texteuro. If you want to use the official version of the Euro symbol, then you have to use eurosym, load it with the official option in the preamble:

\usepackage[official]{eurosym}

then you can insert it with the \euro command. Finally, if you want a Euro symbol that's matching with the current font style (e.g., bold, italics, etc.) but your current font does not provide it, you can use the eurosym package again but with a different option:

\usepackage[gen]{eurosym}

again you can insert the euro symbol with \euro

Ellipsis (…)

A sequence of three dots is known as an ellipsis, which is commonly used to indicate omitted text. On a typewriter, a comma or a period takes the same amount of space as any other letter. In book printing, these characters occupy only a little space and are set very close to the preceding letter. Therefore, you cannot enter ‘ellipsis’ by just typing three dots, as the spacing would be wrong. Instead, there is a special command for these dots. It is called \ldots:

Not like this ... but like this:\\

New York, Tokyo, Budapest, \ldots

|

Ready-made strings

There are some very simple LaTeX commands for typesetting special text strings:

Other symbols

Latex has lots of symbols at its disposal. The majority of them are within the mathematical domain, and later chapters will cover how to get access to them. For the more common text symbols, use the following commands:

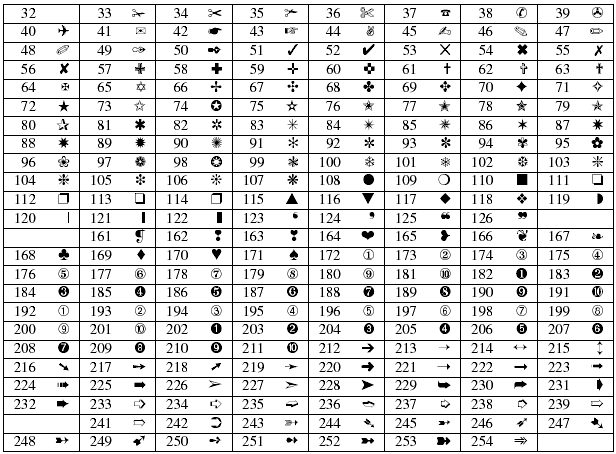

Of course, these are rather boring, and it just so happens that for some more interesting symbols, then the Postscript ZipfDingbats font is available thanks to the pifont. Hopefully, you are beginning to notice now that when you want to use a package, you need to add the declaration to your preamble, in this instance: \usepackage{pifont}. Next, the command \ding{number}, will print the specified symbol. Here is a table of the available symbols:

Paragraph Formatting

Altering the paragraph formatting is not often required, especially in academic writing. However, it is useful to know, and applications tend to be for formatting text in floats, or other more exotic documents.

Paragraph Alignment

Paragraphs in Latex are usually fully justified (i.e., flush with both the left and right margins). For whatever reason, should you wish to alter the justification of a paragraph, there are three environments at hand, and also Latex command equivalents.

| Alignment | Environment | Command |

|---|---|---|

| Left justified | flushleft | \raggedright |

| Right justified | flushright | \raggedleft |

| Center | center | \centering |

All text between the \begin and \end of the specified environment will be justified appropriately. The commands listed are for use within other environments. For example, p (paragraph) columns in tabular.

Paragraph Indents

Paragraph indents are normally fine. The size of the indent is determined by a parameter called \parindent. The default length that this constant holds is set by the document class that you use. It is possible to override using the \setlength command.

\setlength{\parindent}{length}

will reset the indent to length.

Be careful, however, if you decide to set the indent to zero, then it means you will need a vertical space between paragraphs in order to make them clear. The space between paragraphs is held in \parskip, which could be altered in a similar fashion as above. However, this parameter is used elsewhere too, such as in lists, which means you run the risk of making various parts of your document look very untidy (that is, even more untidy than this type of paragraph style!) It may be better to use a document class typeset for this style of indentation, such as artikel3.cls (written by a dutch person, translates to article3).

To indent all the lines of a paragraph other than just the first line, use the TeX command \hangindent. An example follows.

\hangindent=0.7cm This paragraph has an extra indentation at the left.

Line Spacing

To change line spacing in the whole document use the command \linespread covered in LaTeX/Customizing_LaTeX#Spacing.

To change line spacing in specific environments do the following:

- Add

\usepackage{setspace}to the document preamble. - This then provides the following environments to use within your document:

doublespace- all lines are double spaced.onehalfspace- line spacing set to one-and-half spacing.singlespace- normal line spacing.

Special Paragraphs

For those of you who have read most/all of the tutorials so far, you will have already come across some of the following paragraph formats. Although seen before, it makes sense to re-introduce here, for the sake of completeness.

Verbatim Text

There are several ways to introduce text that won't be interpreted by the compiler. If you use the verbatim environment, everything input between the begin and end commands are processed as if by a typewriter. All spaces and new lines are reproduced as given, and the text is displayed in an appropriate fixed-width font. Any LaTeX command will be ignored and handled as plain text. Ideal for typesetting program source code. This environment was used in an example in the previous tutorial. Here is an example:

\begin{verbatim}

The verbatim environment

simply reproduces every

character you input,

including all s p a c e s!

\end{verbatim}

|

Note: once in the verbatim environment, the only command that will be recognized is \end{verbatim}. Any others will be output, verbatim! If this is an issue, then you can use the alltt package instead, providing an environment with the same name:

\begin{alltt}

Verbatim extended with the ability

to use normal commands. Therefore, it

is possible to \emph{emphasize} words in

this environment, for example.

\end{alltt}

|

Remember to add \usepackage{alltt} to your preamble to use it though!

If you just want to introduce a short verbatim phrase, you don't need to use the whole environment, but you have the \verb command:

\verb+my text+

The first character following \verb is the delimiter: here we have used "+", but you can use any character you like but * and space; \verb will print verbatim all the text after it until it finds the next delimiter. For example, the code:

\verb|\textbf{Hi mate!}|

will print \textbf{Hi mate!}, ignoring the effect \textbf should have on text.

For more control over formatting, however, you can try the fancyvrb package, which provides a Verbatim environment (note the capital letter) which lets you draw a rule round the verbatim text, change the font size, and even have typographic effects inside the Verbatim environment. It can also be used in conjunction with the fancybox package and it can add reference line numbers (useful for chunks of data or programming), and it can even include entire external files.

Typesetting URLs

One of either the hyperref or url packages provides the \url command, which properly typesets URLs, for example:

Go to \url{http://www.uni.edu/~myname/best-website-ever.html} for my website.

will show this URL exactly as typed (similar to the \verb command), but the \url command also performs a hyphenless break at punctuation characters. It was designed for Web URLs, so it understands their syntax and will never break mid-way through an unpunctuated word, only at slashes and full stops. Bear in mind, however, that spaces are forbidden in URLs, so using spaces in \url arguments will fail, as will using other non-URL-valid characters.

When using this command through the hyperref package, the URL is "clickable" in the PDF document, whereas it is not linked to the web when using only the url package.

Listing Environment

This is also an extension of the verbatim environment provided by the moreverb package. The extra functionality it provides is that it can add line numbers along side the text. The command: \begin{listing}[step]{first line}. The mandatory first line argument is for specifying which line the numbering shall commence. The optional step is the step between numbered lines (the default is 1, which means every line will be numbered).

To use this environment, remember to add \usepackage{moreverb} to the document preamble.

Multi-line comments

As we have seen, the only way LaTeX allows you to add comments is by using the special character %, that will comment out all the rest of the line after itself. This approach is really time-consuming if you want to insert long comments or just comment out a part of your document that you want to improve later. Using the verbatim package, to be loaded in the preamble as usual:

\usepackage{verbatim}

you can use an environment called comment that will comment out everything within itself. Here is an example:

This is another

\begin{comment}

rather stupid,

but helpful

\end{comment}

example for embedding

comments in your document.

|

This is another example for embedding comments in your document. |

Note that this won’t work inside complex environments, like math for example. You may be wondering, why should I load a package called verbatim to have the possibility to add comments? The answer is straightforward: commented text is not interpreted by the compiler just like verbatim text, the only difference is that verbatim text is introduced within the document, while the comment is just dropped.

Quoting text

LaTeX provides several environments for quoting text, they have small differences and they are aimed for different types of quotations. All of them are indented on either margin, and you will need to add your own quotation marks if you want them. The provided environments are:

quote- for a short quotation, or a series of small quotes, separated by blank lines.

quotation- for use with longer quotes, of more than one paragraph, because it indents the first line of each paragraph.

verse- is for quotations where line breaks are important, such as poetry. Once in, new stanzas are created with a blank line, and new lines within a stanza are indicated using the newline command,

\\. If a line takes up more than one line on the page, then all subsequent lines are indented until explicitly separated with\\.

Abstracts

In scientific publications it is customary to start with an abstract which gives the reader a quick overview of what to expect. LaTeX provides the abstract environment for this purpose. It is available in article and report document classes; it's not available in the book, but it's quite simple to create your own if you really need it.

List Structures

Lists often appear in documents, especially academic, as their purpose is often to present information in a clear and concise fashion. List structures in Latex are simply environments which essentially come in three flavors: itemize, enumerate and description.

All lists follow the basic format:

\begin{list_type}

\item The first item

\item The second item

\item The third etc \ldots

\end{list_type}

All three of these types of lists can have multiple paragraphs per item: just type the additional paragraphs in the normal way, with a blank line between each. So long as they are still contained within the enclosing environment, they will automatically be indented to follow underneath their item.

Itemize

This environment is for your standard bulleted list of items.

\begin{itemize}

\item The first item

\item The second item

\item The third etc \ldots

\end{itemize}

|

Enumerate

The enumerate environment is for ordered lists, where by default, each item is numbered sequentially.

\begin{enumerate}

\item The first item

\item The second item

\item The third etc \ldots

\end{enumerate}

|

Description

The description environment is slightly different. You can specify the item label by passing it as an optional argument (although optional, it would look odd if you didn't include it!). Ideal for a series of definitions, such as a glossary.

\begin{description}

\item[First] The first item

\item[Second] The second item

\item[Third] The third etc \ldots

\end{description}

|

Compacted lists using mdwlist

As you may have noticed, in standard LaTeX document classes, the vertical spacing between items, and above and below the lists as a whole, is more than between paragraphs: it may look odd if the descriptions are too short. If you want tightly-packed lists, use the mdwlist package, which provides "starred" versions of the previous environments, i.e. itemize*, enumerate* and description*. They work exactly in the same way, but the output is different.

Nested Lists

Latex will happily allow you to insert a list environment into an existing one (up to a depth of four). Simply begin the appropriate environment at the desired point within the current list. Latex will sort out the layout and any numbering for you.

\begin{enumerate}

\item The first item

\begin{enumerate}

\item Nested item 1

\item Nested item 2

\end{enumerate}

\item The second item

\item The third etc \ldots

\end{enumerate}

|

Customizing Lists

Customizing many things in LaTeX is not really within the beginners domain. While not necessarily difficult in itself, because beginners are already overwhelmed with the array of commands and environments, moving on to more advanced topics runs the risk of confusion.

However, since the tutorial is on formatting, I shall still include a brief guide on customizing lists. Feel free to skip!

Customizing Enumerated Lists

The thing people want to change most often with Enumerated lists are the counters. Therefore, to go any further, a brief introduction to LaTeX counters is required. Anything that LaTeX automatically numbers, such as section headers, figures, and itemized lists, there is a counter associated with it that controls the numbering. Each counter also has a default format that dictates how it is displayed whenever LaTeX needs to print it. Such formats are specified using internal LaTeX commands:

| Command | Example |

| \arabic | 1, 2, 3 ... |

| \alph | a, b, c ... |

| \Alph | A, B, C ... |

| \roman | i, ii, iii ... |

| \Roman | I, II, III ... |

| \fnsymbol | Aimed at footnotes (see below), but prints a sequence of symbols. |

There are four individual counters that are associated with itemized lists, each one represents the four possible levels of nesting, which are called: enumi, enumii, enumiii, enumiv. Each counter entity holds various bits of information about itself. To get to the numbered element, simply use \the followed immediately (i.e., no space) by the name of the counter, e.g., \theenumi. This is often referred to as the representation of a counter. Also, in order to reset any of these counters in the middle of an enumeration simply use \setcounter. For example to reset enumi use:

\setcounter{enumi}{0}

Now, that's most of the technicalities out of the way. To make changes to the formatting of a given level:

\renewcommand{\representation}{\format_command{counter}}

Admittedly, the generic version is not that clear, so a couple of examples will clarify:

%Redefine the first level

\renewcommand{\theenumi}{\Roman{enumi}}

\renewcommand{\labelenumi}{\theenumi}

%Redefine the second level

\renewcommand{\theenumii}{\Alph{enumii}}

\renewcommand{\labelenumii}{\theenumii}

The method used above first explicitly changes the format used by the counter. However, the element that controls the label needs to be updated to reflect the change, which is what the second line does. Another way to achieve this result is this:

\renewcommand{\labelenumi}{\Roman{enumi}}

This simply redefines the appearance of the label, which is fine, providing that you do not intend to cross-reference to a specific item within the list, in which case the reference will be printed in the previous format. This issue does not arise in the first example.

Customizing Itemised Lists

Itemized lists are not as complex as they do not need to count. Therefore, to customize, you simply change the labels. The itemize labels are accessed via \labelitemi, \labelitemii, \labelitemiii, \labelitemiv, for the four respective levels.

\renewcommand{\labelitemi}{\textgreater}

The above example would set the labels for the first level to a greater than (>) symbol. Of course, the text symbols available in Latex are not very exciting. Why not use one of the ZapfDingbat symbols, as described in the Symbols symbols section. Or use a mathematical symbol:

\renewcommand{\labelitemi}{$\star$}

Itemized list with tightly set items, that is with no vertical space between two consecutive items, can be created as follows.

\begin{itemize}

\setlength{\itemsep}{0cm}%

\setlength{\parskip}{0cm}%

\item Item opening the list

\item Item tightly following

\end{itemize}

Details of Customizing Lists

Note that it is necessary that the \renewcommand appears after the \begin{document} instruction so the changes made are taken into account. This is needed for both enumerated and itemized lists.

Inline lists

Inline lists are a special case as they require the use of the paralist package which provides the inparaenum environment (with an optional formatting specification in square brackets):

Footnotes

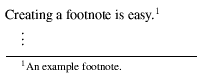

Footnotes are a very useful way of providing extra information to the reader. It is normally non-essential, and so can be placed at the bottom of the page, which means the main body remains concise.

The footnote facility is easy to use. The command you need is: \footnote{text}. Do not leave a space between the command the word where you wish the footnote marker to appear, otherwise Latex will process that space and will leave the output not looking as intended.

Creating a footnote is easy.\footnote{An example footnote.}

|

Latex will obviously take care of typesetting the footnote at the bottom of the page. Each footnote is numbered sequentially - a process that, as you should have guessed by now, is automatically done for you.

It is possible to customize the footnote marking. By default, they are numbered sequentially (Arabic). However, without going too much into the mechanics of Latex at this point, it is possible to change using the following command (of which needs to be placed at the beginning of the document, or at least before the first footnote command is issued).

| \renewcommand{\thefootnote}{\arabic{footnote}} | Arabic numerals, e.g., 1, 2, 3... |

| \renewcommand{\thefootnote}{\roman{footnote}} | Roman numerals (lowercase), e.g., i, ii, iii... |

| \renewcommand{\thefootnote}{\Roman{footnote}} | Roman numerals (uppercase), e.g., I, II, III... |

| \renewcommand{\thefootnote}{\alph{footnote}} | Alphabetic (lowercase), e.g., a, b, c... |

| \renewcommand{\thefootnote}{\Alph{footnote}} | Alphabetic (uppercase), e.g., A, B, C... |

| \renewcommand{\thefootnote}{\fnsymbol{footnote}} | A sequence of nine symbols (try it and see!) |

Margin Notes

I dare say that this is not a commonly used function, however, I thought I'd include it anyway, as it is simple to use command. \marginpar{margin text} will position the enclosed text on to the outside margin. To swap the default side, issue \reversemarginpar and that moves margin notes to the opposite side.

Summary

Phew! What a busy tutorial! A lot of material was covered here, mainly because formatting is such a broad topic. Latex is so flexible that we actually only skimmed the surface, as you can have much more control over the presentation of your document if you wish. Having said that, one of the purposes of Latex is to take away the stress of having to deal with the physical presentation yourself, so you need not get too carried away!