Calculus/Vectors

See also Algebra/Vectors

Two-Dimensional Vectors

Introduction

In most mathematics courses up until this point, we deal with scalars. These are quantities which only need one number to express. For instance, the amount of gasoline used to drive to the grocery store is a scalar quantity because it only needs one number: 2 gallons.

In this unit, we deal with vectors. A vector is a directed line segment -- that is, a line segment that points one direction or the other. As such, it has an initial point and a terminal point. The vector starts at the initial point and ends at the terminal point, and the vector points towards the terminal point. A vector is drawn as a line segment with an arrow at the terminal point:

The same vector can be placed anywhere on the coordinate plane and still be the same vector -- the only two bits of information a vector represents are the magnitude and the direction. The magnitude is simply the length of the vector, and the direction is the angle at which it points. Since neither of these specify a starting or ending location, the same vector can be placed anywhere. To illustrate, all of the line segments below can be defined as the vector with magnitude and angle 45 degrees:

It is customary, however, to place the vector with the initial point at the origin as indicated by the blue vector. This is called the standard position.

Component Form

In standard practice, we don't express vectors by listing the length and the direction. We instead use component form, which lists the height (rise) and width (run) of the vectors. It is written as follows:

From the diagram we can now see the benefits of the standard position: the two numbers for the terminal point's coordinates are the same numbers for the vector's rise and run. Note that we named this vector u. Just as you can assign numbers to variables in algebra (usually x, y, and z), you can assign vectors to variables in calculus. The letters u, v, and w are usually used, and either boldface or an arrow over the letter is used to identify it as a vector.

When expressing a vector in component form, it is no longer obvious what the magnitude and direction are. Therefore, we have to perform some calculations to find the magnitude and direction.

Magnitude

where is the width, or run, of the vector; is the height, or rise, of the vector. You should recognize this formula as pythagorean's theorem. It is -- the magnitude is the distance between the initial point and the terminal point.

The magnitude of a vector can also be called the norm.

Direction

where is the direction of the vector. This formula is simply the tangent formula for right triangles.

Vector Operations

For these definitions, assume:

Vector Addition

Graphically, adding two vectors together places one vector at the end of the other. This is called tip-to-tail addition: The resultant vector, or solution, is the vector drawn from the initial point of the first vector to the terminal point of the second vector when they are drawn tip-to-tail:

Fig:

Numerically:

Scalar Multiplication

Graphically, multiplying a vector by a scalar changes only the magnitude of the vector by that same scalar. That is, multiplying a vector by 2 will "stretch" the vector to twice its original magnitude, keeping the direction the same.

Numerically, you calculate the resultant vector with this formula:

As previously stated, the magnitude is changed by the same constant:

Since multiplying a vector by a constant results in a vector in the same direction, we can reason that two vectors are parallel if one is a constant multiple of the other -- that is, that if for some constant c.

We can also divide by a non-zero scalar by instead multiplying by the reciprocal, as with dividing regular numbers:

Dot Product and Perpendicular Vectors

The dot product, sometimes confusingly called the scalar product, of two vectors is given by:

or alternatively:

where is the angle difference between the two vectors. If this angle is 90 degrees or (if the two vectors are orthogonal to each other), that is the vectors are perpendicular, then the dot product is 0.

The dot product of a vector with itself is given by:

Unit Vectors

A unit vector is a vector with a magnitude of 1. The unit vector of u is a vector in the same direction as , but with a magnitude of 1:

The process of finding the unit vector of u is called normalization. As mentioned in scalar multiplication, multiplying a vector by constant C will result in the magnitude being multiplied by C. We know how to calculate the magnitude of . We know that dividing a vector by a constant will divide the magnitude by that constant. Therefore, if that constant is the magnitude, dividing the vector by the magnitude will result in a unit vector in the same direction as :

, where is the unit vector of

Standard Unit Vectors

There are two special unit vectors. i points one unit directly right in the x direction, and j points one unit directly up in the y direction:

Using the scalar multiplication and vector addition rules, we can then express vectors in a different way:

If we work that equation out, it makes sense. Multiplying x by i will result in the vector . Multiplying y by j will result in the vector . Adding these two together will give us our original vector, . Expressing vectors using i and j is called standard form.

Projections

Sometimes it is necessary to find the part of a vector parallel to another which is known as the projection of a vector on (notationally displayed as ).

To determine the projection we first note that is proportional to . In other words:

Also, with the angle θ, and because of the definition of the cosine:

By the dot product:

By substituting this for θ and then the new expression for into the equation relating it for c, we find that:

Which, finally, substituting this c in the oringinal vector-form equation gives us the widely used definition for :

Polar coordinates

Polar coordinates are an alternative two-dimensional coordinate system, which is often useful when rotations are important. Instead of specifying the position along the x and y axes, we specify the distance from the origin, r, and the direction, an angle θ.

Looking at this diagram, we can see that the values of x and y are related to those of r and θ by the equations

Because tan-1 is multivalued, care must be taken to select the right value.

Just as for Cartesian coordinates the unit vectors that point in the x and y directions are special, so in polar coordinates the unit vectors that point in the r and θ directions are also special.

We will call these vectors and , pronounced r-hat and theta-hat. Putting a circumflex over a vector this way is often used to mean the unit vector in that direction.

Again, on looking at the diagram we see,

Three-Dimensional Coordinates and Vectors

Basic definition

Two-dimensional Cartesian coordinates as we've discussed so far can be easily extended to three-dimensions by adding one more value: 'z'. If the standard (x,y) coordinate axes are drawn on a sheet of paper, the 'z' axis would extend upwards off of the paper.

Similar to the two coordinate axes in two-dimensional coordinates, there are three coordinate planes in space. These are the xy-plane, the yz-plane, and the xz-plane. Each plane is the "sheet of paper" that contains both axes the name mentions. For instance, the yz-plane contains both the y and z axes and is perpendicular to the x axis.

Therefore, vectors can be extended to three dimensions by simply adding the 'z' value.

To facilitate standard form notation, we add another standard unit vector:

Again, both forms (component and standard) are equivalent.

Magnitude: Magnitude in three dimensions is the same as in two dimensions, with the addition of a 'z' term in the radicand.

Three dimensions

The polar coordinate system is extended into three dimensions with two different coordinate systems, the cylindrical and spherical coordinate systems, both of which include two-dimensional or planar polar coordinates as a subset. In essence, the cylindrical coordinate system extends polar coordinates by adding an additional distance coordinate, while the spherical system instead adds an additional angular coordinate.

Cylindrical coordinates

The cylindrical coordinate system is a coordinate system that essentially extends the two-dimensional polar coordinate system by adding a third coordinate measuring the height of a point above the plane, similar to the way in which the Cartesian coordinate system is extended into three dimensions. The third coordinate is usually denoted h, making the three cylindrical coordinates (r, θ, h).

The three cylindrical coordinates can be converted to Cartesian coordinates by

Spherical coordinates

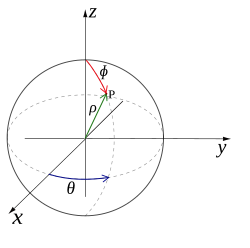

Polar coordinates can also be extended into three dimensions using the coordinates (ρ, φ, θ), where ρ is the distance from the origin, φ is the angle from the z-axis (called the colatitude or zenith and measured from 0 to 180°) and θ is the angle from the x-axis (as in the polar coordinates). This coordinate system, called the spherical coordinate system, is similar to the latitude and longitude system used for Earth, with the origin in the centre of Earth, the latitude δ being the complement of φ, determined by δ = 90° − φ, and the longitude l being measured by l = θ − 180°.

The three spherical coordinates are converted to Cartesian coordinates by

Cross Product

The cross product of two vectors is a determinant:

and is also a pseudovector.

The cross product of two vectors is orthogonal to both vectors. The magnitude of the cross product is the product of the magnitude of the vectors and the sin of the angle between them.

This magnitude is the area of the parallelogram defined by the two vectors.

The cross product is linear and anticommutative. For any numbers a and b,

If both vectors point in the same direction, their cross product is zero.

Triple Products

If we have three vectors we can combine them in two ways, a triple scalar product,

and a triple vector product

The triple scalar product is a determinant

If the three vectors are listed clockwise, looking from the origin, the sign of this product is positive. If they are listed anticlockwise the sign is negative.

The order of the cross and dot products doesn't matter.

Either way, the absolute value of this product is the volume of the parallelepiped defined by the three vectors, u, v, and w

The triple vector product can be simplified

This form is easier to do calculations with.

The triple vector product is not associative.

There are special cases where the two sides are equal, but in general the brackets matter. They must not be omitted.

Three-Dimensional Lines and Planes

We will use r to denote the position of a point.

The multiples of a vector, a all lie on a line through the origin. Adding a constant vector b will shift the line, but leave it straight, so the equation of a line is,

This is a parametric equation. The position is specified in terms of the parameter s.

Any linear combination of two vectors, a and b lies on a single plane through the origin, provided the two vectors are not colinear. We can shift this plane by a constant vector again and write

If we choose a and b to be orthonormal vectors in the plane (i.e unit vectors at right angles) then s and t are Cartesian coordinates for points in the plane.

These parametric equations can be extended to higher dimensions.

Instead of giving parametric equations for the line and plane, we could use constraints. E.g, for any point in the xy plane z=0

For a plane through the origin, the single vector normal to the plane, n, is at right angle with every vector in the plane, by definition, so

is a plane through the origin, normal to n.

For planes not through the origin we get

A line lies on the intersection of two planes, so it must obey the constraint for both planes, i.e

These constraint equations con also be extended to higher dimensions.

Vector-Valued Functions

Vector-Valued Functions are functions that instead of giving a resultant scalar value, give a resultant vector value. These aid in the create of direction and vector fields, and are therefore used in physics to aid with visualizations of electric, magnetic, and many other fields. They are of the following form:

Introduction

Limits, Derivatives, and Integrals

Put simply, the limit of a vector-valued function is the limit of its parts.

Proof:

Suppose

Therefore for any there is a such that

But by the triangle inequality

So

Therefore A similar argument can be used through parts a_n(t)

Now let again, and that for any ε>0 there is a corresponding φ>0 such 0<|t-c|<φ implies

Then

therefore!:

From this we can then create an accurate definition of a derivative of a vector-valued function:

The final step was accomplished by taking what we just did with limits.

By the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus integrals can be applied to the vector's components.

In other words: the limit of a vector function is the limit of its parts, the derivative of a vector function is the derivative of its parts, and the integration of a vector function is the integration of it parts.

Velocity, Acceleration, Curvature, and a brief mention of the Binormal

Assume we have a vector-valued function which starts at the origin and as its independent variables changes the points that the vectors point at trace a path.

We will call this vector , which is commonly known as the position vector.

If then represents a position and t represents time, then in model with Physics we know the following:

is displacement. where is the velocity vector. is the speed. where is the acceleration vector.

The only other vector that comes in use at times is known as the curvature vector.

The vector used to find it is known as the unit tangent vector, which is defined as or shorthand .

The vector normal to this then is .

We can verify this by taking the dot product

Also note that

and

and

Then we can actually verify:

Therefore is perpendicular to

What this gives rise to is the Unit Normal Vector of which the top-most vector is the Normal vector, but the bottom half is known as the curvature. Since the Normal vector points toward the inside of a curve, the sharper a turn, the Normal vector has a large magnitude, therefore the curvature has a small value, and is used as an index in civil engineering to reflect the sharpness of a curve (clover-leaf highways, for instance).

The only other thing not mentioned is the Binormal that occurs in 3-d curves , which is useful in creating planes parallel to the curve.