C++ Programming/Data Type Storage

Internal storage of data types

Bits and Bytes

The byte is the smallest individual piece of data that we can access or modify on a computer. The computer only works on bytes or groups of bytes, never on bits. If you want to modify individual bits, you have to use binary operations on the whole byte that tell the computer how to modify individual bits, but the operation is still done on whole bytes. Before getting too far ahead of ourselves, we'll look at the internal representation of a byte.

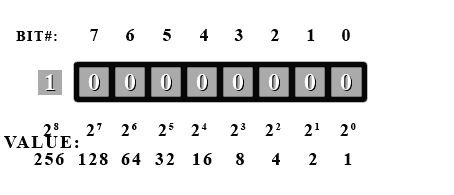

Here's a look at a byte as the computer stores it.

There is actually quite a lot of information here. A byte (usually) contains 8 bits. A bit can only have a value of 0 or 1. The bit number is used to label each bit in the byte (so that we can tell which bit we are talking about). You may be wondering why the bits are labeled from 7 to 0 instead of 0 to 7 or even 1 to 8. The reason 0 is used is because computers always start counting at 0. Technically, we COULD start counting at 1, but this would go against the counting nature of the computer. It is simply more convenient to use 0 for computers as we shall see. Now as to why we numbered them in descending order. In decimal numbers (normal base 10), we put the more significant digits to the left. Example: 254. The 2 here is more significant than the other digits because it represents hundreds as opposed to tens for the 5 or singles for the 4. The same is done in binary. The more significant digits are put towards the left. Counting in binary and in decimal is done in exactly the same manner, except that in binary, instead of counting from 0 to 9, we only count from 0 to 1. If we want to count higher than 1, then we need a more significant digit to the left. In decimal, when we count beyond 9, we need to add a 1 to the next significant digit. It sometimes may look confusing or different only because we as humans are used to counting with 10 digits. In binary, there are only 2 digits, but counting is done by the exact same principles as counting in decimal.

In decimal, each digit represents multiple of a power of 10. Let's take another look at the decimal number 254.

- The 4 represents four multiples of one ( since ).

- Since we're working in decimal (base 10), the 5 represents five multiples of 10 ()

- Finally the 2 represents two multiples of 100 ()

All this is elementary. The key point to recognize is that as we move from right to left in the number, the significance of the digits increases by a multiple of 10. This should be obvious when we look at the following equation:

Do you see any similarities between this and the diagram above? In binary, each digit can only be one of two possibilities (0 or 1), therefore when we work with binary we work in base 2 instead of base 10. So, to convert the binary number 1101 to decimal we can use the following base 10 equation, which you should find very much like the one above:

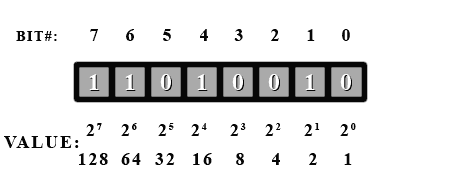

So, to convert the number we simply add the bit values () where a 1 shows up. Let's take a look at our example byte again, and try to find its value in decimal.

First off, we see that bit #5 is a 1, so we have in our total. Next we have bit#3, so we add . This gives us 40. Then next is bit#2, so 40 + 4 is 44. And finally is bit#0 to give 44 + 1 = 45. So this binary number is 45 in decimal.

As can be seen, it is impossible for different bit combinations to give the same decimal value. Here is a quick example to show the relationship between counting in binary (base 2) and counting in decimal (base 10). The bases that these numbers are in are shown in subscript to the right of the number.

=

=

=

=

Data and Variables

When programming in C++, we need a way to store data that can be manipulated by our program. Data comes in a variety of formats, so the compiler needs a way to differentiate between the different types. Right now, we'll concentrate on using bytes. The type name for a byte in C++ is 'char'. It's called char because a byte is often used to represent characters. We won't go into that right now. We only want to use it for its numerical representation.

Let's write a program that will print each value that a byte can hold. How do we do that? We could write a loop that goes from 0 to 255. We'll set our byte to 0 and add one to it every time through the loop. As a side note, do you know what would happen if you added 1 to 255? No combination will represent 256 unless we add more bits. If you look at the diagram above, you will see that the next value (if we could have another digit) would be 256. So our byte would look like this.

But this bit (bit#8) doesn't exist. So where does it go? It actually goes into the carry bit. The carry bit, you say? The processor of the computer has an internal bit used exclusively for carry operations such as this. So if you add 1 to 255 stored in a byte, you'd get 0 with the carry bit set in the CPU. Of course, being a C++ programmer, you never get to use this bit directly. You'll need to learn assembler if you want to do that, but that's a whole other ball game.

In our program, we can start off with a value of 0 and wait until it becomes 0 again before exiting. This will make sure we go through every value a byte can hold.

Inside your main() function, write the following. Don't worry about the loop just yet. We are more concerned with the output right now.

char b=0;

do

{

cout << (int)b << " ";

b++;

if ((b&15)==0) cout << endl;

} while(b!=0);

b is our byte and we initialize it to 0. Inside the loop we print its value. We cast it to an int so that a number is printed instead of a character. Don't worry about casting or int's right now. The next line increments the value in our byte b. Then we print a new line (carriage return/endl) after every 16 numbers. We do this so that we can see all 256 values on the screen at once.

If you were to run this program, you would notice something strange. After 127, we got -128! Negative numbers! Where did these come from? Well, it just so happens that the compiler needs to be told if we're using numbers that can be negative or number that can only be positive. These are called signed and unsigned numbers respectively. By default, the compiler assumes we want to use signed numbers unless we explicitly tell it otherwise. To fix our little problem, add "unsigned" in front of the declaration for b so that it reads: "unsigned char b=0;" (without the quotes). Problem solved!

Two's Complement

Two's complement is a way to store negative numbers in a pure binary representation. The reason that the two's complement method of storing negative numbers was chosen is because this allows the CPU to use the same add and subtract instructions on both signed and unsigned numbers.

To convert a positive number into it's negative two's complement format, you begin by flipping all the bits in the number (1's become 0's and 0's become 1's) and then add 1. (This also works to turn a negative number back into a positive number Ex: -34 into 34 or vice-versa).

Let's try to convert our number 45.

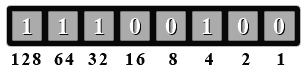

First, we flip all the bits...

And add 1.

Now if we add up the values for all the one bits, we get... 128+64+16+2+1=211? What happened here? Well, this number actually is 211. It all depends on how you interpret it. If you decide this number is unsigned, then it's value is 211. But if you decide it's signed, then it's value is -45. It is completely up to you how you treat the number.

If and only if you decide to treat it as a signed number, then look at the msb (most significant bit [bit#7]). If it's a 1, then it's a negative number. If it's a 0, then it's positive. In C++, using "unsigned" in front of a type will tell the compiler you want to use this variable as an unsigned number, otherwise it will be treated as signed number.

Now, if you see the msb is set, then you know it's negative. So convert it back to a positive number to find out it's real value using the process just described above.

Let's go through a few examples.

Treat the following number as an unsigned byte. What is it's value in decimal?

Since this is an unsigned number, no special handling is needed. Just add up all the values where there's a 1 bit. 128+64+32+4=228. So this binary number is 228 in decimal.

Now treat the number above as a signed byte. What is its value in decimal?

Since this is now a signed number, we first have to check if the msb is set. Let's look. Yup, bit #7 is set. So we have to do a two's complement conversion to get it's value as a positive number (then we'll add the negative sign afterwards).

Ok, so let's flip all the bits...

And add 1. This is a little trickier since a carry propagates to the third bit. For bit#0, we do 1+1 = 10 in binary. So we have a 0 in bit#0. Now we have to add the carry to the second bit (bit#1). 1+1=10. bit#1 is 0 and again we carry a 1 over to the bit (bit#2). 0+1 = 1 and we're done the conversion.

Now we add the values where there's a one bit. 16+8+4 = 28. Since we did a conversion, we add the negative sign to give a value of -28. So if we treat 11100100 (base 2) as a signed number, it has a value of -28. If we treat it as an unsigned number, it has a value of 228.

Let's try one last example.

Give the decimal value of the following binary number both as a signed and unsigned number.

First as an unsigned number. So we add the values where there's a 1 bit set. 4+1 = 5. For an unsigned number, it has a value of 5.

Now for a signed number. We check if the msb is set. Nope, bit #7 is 0. So for a signed number, it also has a value of 5.

As you can see, if a signed number doesn't have its msb set, then you treat it exactly like an unsigned number.

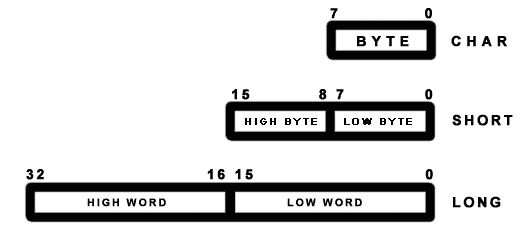

Endian

Now that we've seen many ways to use a byte, it is time to look at ways to represent numbers larger than 255. By grouping bytes together, we can represent numbers that are much larger than 255. If we use 2 bytes together, we double the number of bits in our number. In effect, 16 bits allows us to represent numbers up to 65535 (unsigned). And 32 bits allows us to represent numbers above 4 billion. We already saw the type for a byte. It is called a 'char'.

Here are a few basic primitive types:

1. char (1 byte (by definition), max unsigned value: at least 255)

2. short int (at least 16 bits, max unsigned value: at least 65535)

3. long int (at least 32 bits, max unsigned value: at least 4294967295)

4. float (typically 4 bytes, floating point)

5. double (typically 8 bytes, floating point)

For 'short int' and 'long int', you can leave out the 'int' because the compiler will know what type you want. You can also use 'int' by itself and it will default to whatever your compiler is set at for an int. On most recent compilers, int defaults to a 32-bit type.

All of the topics explained above also apply to short int's and long int's. The difference is simply the number of bits used is different and the msb is now bit#15 for a short and bit#31 for a long (assuming a 32-bit long type).

Let's look at a (16-bit) short. You may think that in memory the byte for bits 15 to 8 would be followed by the byte for bits 7 to 0 (because bits 15 to 8 appears first). In other words, byte #0 would be the high byte and byte #1 would be the low byte. This is true for some other systems. For example, the Motorola 68000 series CPUs do work this way. The Amiga and old Macintoshes use the M68000 and they indeed do use this byte ordering.

However, on PCs (with 8088/286/386/486/Pentiums) this is not so. The ordering is reversed so that the low byte comes before the high byte. The byte that represents bits 0 to 7 always comes before all other bytes on PCs. This is called little-endian ordering. The other ordering, such as on the M68000, is called big-endian ordering. This is very important to remember when doing low level byte operations.

For big-endian computers, the basic idea is to keep the higher bits on the left or in front. For little-endian computers, the idea is to keep the low bits in the low byte. There is no inherent advantage to either scheme except perhaps for an oddity. Using a little-endian long int as a smaller type in is theoretically possible as the low byte(s) is/are always in the same location (first byte). With big-endian the low byte is always located differently depending on the size of the type. For example (in big-endian), the low byte is the byte in a long int and the byte in a short int. So a proper cast must be done and low level tricks become rather dangerous.

Floating point representation

A generic real number with a decimal part can also be expressed in binary format. For instance 110.01 in binary corresponds to:

Exponential notation (also known as scientific notation, or standard form, when used with base 10, as in ) can be also used and the same number expressed as:

When there is only one non-zero digit on the left of the decimal point, the notation is termed normalized.

In computing applications a real number is represented by a sign bit (S) an exponent (e) and a mantissa (M). The exponent field needs to represent both positive and negative exponents. To do this, a bias E is added to the actual exponent in order to get the stored exponent, and the sign bit (S), which indicates whether or not the number is negative, is transformed into either +1 or -1, giving s. A real number is thus represented as:

S, e and M are concatenated one after the other in 32-bit words to create a float number and in 64-bit words to create a double one. For the float type 8 bits are used for the exponent and 23 bits for the mantissa and the exponent offset is E=127. For the double type 11 bits are used for the exponent and 53 for the mantissa and the exponent offset is E=1023. Note that, the (non-zero) digit before the decimal point in the normalized binary representation has to be 1, so it is not stored as part of the mantissa.

For instance the binary representation of the number 5.0 (using float type) is:

0 10000001 01000000000000000000000

The first bit is 0, meaning the number is positive, the exponent is 129-127=2, and the mantissa is 1.01 (note the leading one is not included in the binary representation). 1.01 corresponds to 1.25 in decimal representation. Hence 1.25*4=5.