Calculus/Continuity

Defining Continuity

We are now ready for a formal definition of continuity, which was introduced in our review of functions. The definition is simple:

|

If is defined on an open interval containing c. |

Note that for f to be continuous at c, the definition requires three conditions:

- that f is defined at c, so f(c) exists,

- the limit as x approaches c exists, and

- the limit and f(c) are equal.

If any of these do not hold then f is not continuous at c.

Notice how this relates to the intuitive idea of continuity. To be continuous, we want the graph of the function to approach the actual value of the function. This can be done by graphing the function itself. If the function is uniformly "smooth" (i.e. no "gaps", breaks, or sharp turns/corners) within an interval, then it is also continuous.

|

A function is said to be "continuous" if it is continuous at |

Discontinuities

A discontinuity is a point where a function is not continuous.

Removable discontinuities

For example, the function is considered to have a removable discontinuity at x = 3. It is discontinuous at that point because the fraction then becomes which is undefined. Therefore the function fails the very first definition of continuity.

Why do we call it removable though? Because, if we modify the function slightly, we can eliminate the discontinuity and make the function continuous.

To make the function f(x) continuous, we have to simplify f(x) so that .

As long as x ≠ 3, we can simplify the function f(x) to get a new function g(x) where

Note that the function g(x) is not the same as the original function f(x), because g(x) has the extra point (3, 6). g(x) is now defined for x=3, the only thing keeping f(x) from being continuous. In fact, this kind of simplification is always possible with a removable discontinuity in a rational function. When the denominator is not 0, we can divide through to get a function which is the same. When it is 0, this new function will be identical to the old except for new points where previously we had division by 0.

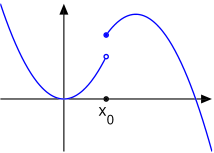

Jump Discontinuities

Unfortunately, there are those discontinuities which cannot be removed from a function. Consider this k(x):

k(x) is certainly defined for all points c, and the limit as x approaches any c even exists, the problem then lies in the fact that the limit and the function do not always equal each-other. Specifically

- But k(x) actually equals 1 at x=0, so...

- And the function is discontinuous.

Sadly there is no way to remove these discontinuities without fatally altering the function. There are no algebraic transformations to be applied and the function simply has to be accepted as discontinuous, ruling out many operations that will be introduced throughout calculus. These discontinuities are called nonremovable or essential discontinuities.

One-Sided Continuity

Just as a function can have a one-sided limit, a function can be continuous from a particular side.

Intermediate value theorem (IVT)

The intermediate value theorem is a very important theorem in calculus and analysis. It says:

| If a function is continuous on a closed interval [a,b], then for every value k between f(a) and f(b) there is a value c on [a,b] such that f(c)=k. |

Application: bisection method

The bisection method is the simplest and most reliable algorithm to find roots to an equation.

Suppose we want to solve the equation f(x) = 0. Given two points a and b such that f(a) and f(b) have opposite signs, we know by the intermediate value theorem that f must have at least one root in the interval [a, b] as long as f is continuous on this interval. The bisection method divides the interval in two by computing c = (a+b) / 2. There are now two possibilities: either f(a) and f(c) have opposite signs, or f(c) and f(b) have opposite signs. The bisection algorithm is then applied recursively to the sub-interval where the sign change occurs. In this way we home in to a small sub-interval containing the root. The mid point of that small sub-interval is usually taken as the root.