Circuit Theory/Laplace Transform

Laplace Transform

The Laplace Transform is a powerful tool for an Electrical Engineer to use. The transform allows equations in the "time domain" to be transformed into an equivalent equation in the Complex S Domain. The laplace transform is an integral transform, although the reader does not need to have a knowledge of integral calculus because all results will be provided. This page will discuss the Laplace transform as being simply a tool for solving and manipulating ordinary differential equations.

Laplace transformations of circuit elements are similar to phasor representations, but they are not the same. Laplace transformations are more general than phasors, and can be easier to use in some instances. Also, do not confuse the term "Complex S Domain" with the complex power ideas that we have been talking about earlier. Complex power uses the variable , while the Laplace transform uses the variable s. The Laplace variable s has nothing to do with power.

The transform is named after the mathematician Pierre Simon Laplace, who lived in the 18th century. The transform itself did not become popular until Oliver Heaviside, a famous electrical engineer, began using a variation of it to solve electrical circuits.

The Transform

The mathematical definition of the laplace transform is as follows:

The transform, by virtue of the definite integral, removes all t from the resulting equation, leaving instead the new variable s. In essence, this transform takes the function f(t), and "transforms it" into a function in terms of s, F(s). As a general rule the transform of a function f(t) is written as F(s). Time-domain functions are written in lower-case, and the resultant S-domain functions are written in upper-case.

we will use the following notation to show the transform of a function:

We use this notation, because we can convert F(s) back into f(t) using the inverse Laplace transform.

The Inverse Transform

The inverse laplace transform converts a function in the complex S-domain to its counterpart in the time-domain. Its mathematical definition is as follows:

where is a real constant such that all of the poles of fall in the region . In other words, is chosen so that all of the poles of are to the left of the vertical line intersecting the real axis at .

The inverse transform is more difficult mathematically than the transform itself is. However, luckily for us, extensive tables of laplace transforms and their inverses have been computed, and are available for easy browsing.

Laplace Domain

The Laplace domain, or the "Complex s Domain" is the domain into which the Laplace transform transforms a time-domain equation. s is a complex variable, composed of real parts:

The Laplace domain graphs the real part (σ) as the horizontal axis, and the imaginary part (ω) as the vertical axis. The real and imaginary parts of s can be considered as independant quantities.

Transform Properties

The most important property of the Laplace Transform (for now) is as follows:

Likewise, we can express higher-order derivatives in a similar manner:

In plain english, the laplace transform converts differentiation into polynomials. The only important thing to remember is that we must add in the initial conditions of the time domain function, but for most circuits, the initial condition is 0, leaving us with nothing to add.

For integrals, we get the following:

Initial Value Theorem

The Initial Value Theorem of the laplace transform states as follows:

This is useful for finding the initial conditions of a function needed when we perform the transform of a differentiation operation (see above).

Final Value Theorem

Similar to the Initial Value Theorem, the Final Value Theorem states that we can find the value of a function f, as t approaches infinity, in the laplace domain, as such:

This is useful for finding the steady state response of a circuit. The final value theorem may only be applied to stable systems.

Transfer Function

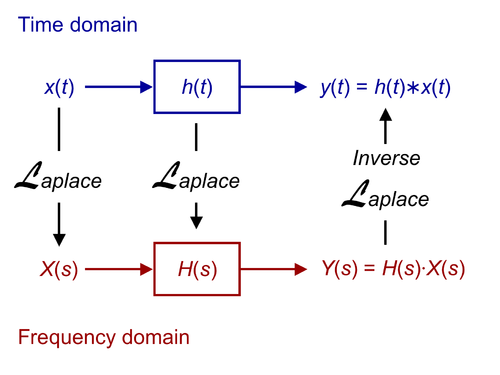

If we have a circuit with impulse-response h(t) in the time domain, with input x(t) and output y(t), we can find the Transfer Function of the circuit, in the laplace domain, by transforming all three elements:

In this situation, H(s) is known as the "Transfer Function" of the circuit. It can be defined as both the transform of the impulse response, or the ratio of the circuit input to it's output in the Laplace domain:

Transfer functions are powerful tools for analyzing circuits. If we know the transfer function of a circuit, we have all the information we need to understand the circuit, and we have it in a form that is easy to work with. When we have obtained the transfer function, we can say that the circuit has been "solved" completely.

Convolution Theorem

Earlier it was mentioned that we could compute the output of a system from the input and the impulse response by using the convolution operation. As a reminder, given the following system:

Template:Circuit Theory ASCII Sys

We can calculate the output using the convolution operation, as such:

Where the asterisk denotes convolution, not multiplication. However, in the S domain, this operation becomes much easier, because of a property of the laplace transform:

Where the asterisk operator denotes the convolution operation. This leads us to an english statement of the convolution theorem:

Now, if we have a system in the Laplace S domain:

Template:Circuit Theory ASCII Trans

We can compute the output Y(s) from the input X(s) and the Transfer Function H(s):

Notice that this property is very similar to phasors, where the output can be determined by multiplying the input by the network function. The network function and the transfer function then, are very similar quantities.

Resistors

The laplace transform can be used independently on different circuit elements, and then the circuit can be solved entirely in the S Domain (Which is much easier). Let's take a look at some of the circuit elements:

Resistors are time and frequency invariant. Therefore, the transform of a resistor is the same as the resistance of the resistor:

Compare this result to the phasor impedance value for a resistance r:

You can see very quickly that resistance values are very similar between phasors and laplace transforms.

Ohm's Law

If we transform Ohm's law, we get the following equation:

Now, following ohms law, the resistance of the circuit element is a ratio of the voltage to the current. So, we will solve for the quantity , and the result will be the resistance of our circuit element:

This ratio, the input/output ratio of our resistor is an important quantity, and we will find this quantity for all of our circuit elements. We can say that the transform of a resistor with resistance r is given by:

Capacitors

Let us look at the relationship between voltage, current, and capacitance, in the time domain:

Solving for voltage, we get the following integral:

Then, transforming this equation into the laplace domain, we get the following:

Again, if we solve for the ratio , we get the following:

Therefore, the transform for a capacitor with capacitance C is given by:

Inductors

Let us look at our equation for inductance:

putting this into the laplace domain, we get the formula:

And solving for our ratio , we get the following:

Therefore, the transform of an inductor with inductance L is given by:

Impedance

Since all the load elements can be combined into a single format dependant on s, we call the effect of all load elements impedance, the same as we call it in phasor representation. We denote impedance values with a capital Z (but not a phasor ).