Electronics/DC Voltage and Current

Ohm's Law

Ohm's law describes the relationship between voltage, current, and resistance.

Voltage and current are proportional at a given temperature:

Voltage (V) is measured in volts (V); Current (I) in amperes (A); and resistance (R) in ohms (Ω).

In this example, the current going through any point in the circuit, I, will be equal to the voltage V divided by the resistance R.

In this example, the voltage across the resistor, V, will be equal to the supplied current, I, times the resistance R.

If two of the values (V, I, or R) are known, the other can be calculated using this formula.

Any more complicated circuit has an equivalent resistance that will allow us to calculate the current draw from the voltage source. Equivalent resistance is worked out using the fact that all resistor are either in parallel or series. Similarly, if the circuit only has a current source, the equivalent resistance can be used to calculate the voltage dropped across the current source.== Kirchoff's Voltage Law ==

Kirchoff's Voltage Law (KVL): The sum of voltage drops around any loop in the circuit that starts and ends at the same place must be zero.

When you have a positive potential on one side of a battery, then there must be a negative potential on the other side of the battery.

(With Kirchoff's law, it's the sum of the voltages around the entire loop -- including the battery -- that equals zero. So, say you just have a 9 Volt battery connected to a resistor: there's 9V across the resistor, and 9V across the battery; the directions work out so that they subtract: 9V − 9V = 0.)

Analogy to elevation: A person is at the bottom of a mountain. They walk up the mountain, down the other side, and around to their starting position. Even though they changed elevation during the walk, they are at the same elevation as when they started.

KVL Example

- Insert diagram and example here: A voltage source and two resistors in series. Calculate the voltage across each component using ohm's law and the students knowledge of resistors in series, then start at ground, add the voltage source, and then subtract the drops across each resistor, and show that it comes back to zero.

Voltage as a Physical Quantity

Voltage is the potential difference between two charged objects.

- You really should put in something here about voltage being equal to the electric field times distance. It's the analogue equation of the gravitational potential of an object equalling the gravitational field times height.

- Yeah. It should go in the Basic Concepts section, though. Analogies are always good.

- Another way of thinking about voltage is potential energy per unit of charge. This gives a similar connection to gravitational potential -- to get the potential energy you multiply gravitational potential by mass or multiply the electrical potential by charge. In addition, it gives a connection to p=iv. Power is a change in energy divided by time. Voltage times current is the same as voltage*charge / time, which is energy divided by time.

The nice things about potentials is you can add or subtract them in series to make larger or smaller potentials as is commonly done in batteries.

Electrons flow from areas of high potential to lower potential.

At a given place in a circuit there are numerous paths to ground (what about negative voltages?). Each of them has the same voltage as they have the same potential from ground (why?) (-> because of KVL).

All the components of a circuit have resistance that acts as a potential drop.

Additional note: The following explains why voltage is "analogous" to the pressure of a fluid in a pipe (although, of course, it is only an analogy, not exactly same thing), and it also explains the strange-sounding "dimensions" of voltage. Consider the potential energy of compressed air being pumped into tank. The energy increases with each new increment of air. Pressure is that energy divided by the volume, which we can understand intuitively. Now consider the energy of electric charge (measured in coulombs) being forced into a capacitor. Voltage is that energy per charge, so voltage is analogous to a pressure-like sort of forcefulness. Also, dimensional analysis tells us that voltage ("energy per charge") divides out to be "charge per distance," the distance being between the plates of the capacitor. (More discussion is on page 16 of "Industrial Electronics," by D. J. Shanefield, Noyes Publications, Boston, 2001.)

Kirchoff's Current Law

Kirchoff's Current Law (KCL): The sum of all current entering a node must equal the sum of all currents leaving the node.

Kirchoff's current law can be described with a sentence as "What comes in, must go out". It's that simple.

This means that current is conserved. If you have a current into a junction, the same current must go out of the junction.

Analogy to traffic: The number of cars entering an intersection is equal to the number of cars leaving the intersection.

KCL Example

-I1 + I2 + I3 = 0 ↔ I1 = I2 + I3

I1 - I2 - I3 - I4 = 0 ↔ I2 + I3 + I4 = I1

Here is more about Kirchhoff's laws, which can be integrated here

Consequences of KVL and KCL

Voltage Dividers

If two circuit elements are in series, there is a voltage drop across each element, but the current through both must be the same. The voltage at any point in the chain divides according to the resistances. A simple circuit with two (or more) resistors in series with a source is called a voltage divider.

Figure A: Voltage Divider circuit.

Consider the circuit in Figure A. According to KVL the voltage is dropped across resistors and . If a current i flows through the two series resistors then by Ohm's Law.

- .

So

Therefore

Similary if is the voltage across then

In general for n series resistors the voltage dropped across one of them say is

Where

Voltage Dividers as References

Clearly voltage dividers can be used as references if you have a 9 volt battery and you want 4.5 volts then connect two equal valued resistors in series and take the reference across the second and ground. There are clearly other concerns though the first concern is current draw and the effect of the source impedance clearly connecting two 100 ohm resistors is a bad idea if the source impedance is say 50 ohms. Then the current draw would be 0.036 mA which is quite large if the battery is rated say 200 milliampere hours. The loading is more annoying with that source impedance too, the reference voltage with that source impedance is . So clearly increasing the order of the resistor to at least 1 k is the way to go to reduce the current draw and the effect of loading. The other problem with these voltage divider references is that the reference cannot be loaded if we put a 100 Ω resistor in parallel with a 10 kΩ resistor, when the voltage divider is made of two 10 kΩ resistors, then the resistance of the reference resistor becomes somewhere near 100 Ω. This clearly means a terrible reference. If a 10 MΩ resistor is used for the reference resistor will still be some where around 10 kΩ but still probably less. The effect of tolerances is also a problem; if the resistors are rated 5% then the resistance of 10 kΩ resistors can vary by ±500 Ω. This means more inaccuracy with this sort of reference.

Current Dividers

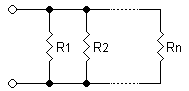

If two elements are in parallel, the voltage across them must be the same, but the current divides according to the resistances. A simple circuit with two (or more) resistors in parallel with a source is called a current divider.

Figure B: Parallel Resistors.

If a voltage V appears across the resistors in Figure B with only and for the moment then the current flowing in the circuit, before the division, i is according to Ohms Law.

Using the equivalent resistance for a parallel combination of resistors is

- (1)

The current through according to Ohms Law is

- (2)

Dividing equation (2) by (1)

Similarly

In general with n Resistors the current is

Or possibly more simply

Where