Nature/Law

Citations

- The supreme task of the physicist is to arrive at those universal elementary laws from which the cosmos can be built up by pure deduction. There is no logical path to these laws; only intuition, resting on sympathetic understanding of experience, can reach them. Albert Einstein

What is a law of nature ? Introduction

During history of the human culture and science rules about nature were found and stored. Among those rules there were very simple laws, as for example the sentence:

On earth every held up object falls down to the ground, unless it can fly or it is lighter than air or it is fixed firmly.

Many of these rules were clear to everyone without big thinking: Nearly each human being knew that hungry lions are dangerous. Many of these rules had to be reformulated again and again, since they proved as partly wrong. Some rules were also completely rejected, since they were completely wrong . A famous example of it was the idea: The earth is the center of the universe and the sun moves around the earth. This idea had to be overcome during a long painful process.

A big improvement in the development of scientific rules was the moment when the scientists started to ask questions and answered them by experiments. The speculations became less and less, the experiments and observations became more and more. Some parts of nature however where out of reach for experiments , since the objects were too far away or too heavy.

A further improvement was the idea to formulate laws of nature mathematically. In particular physical laws were easily translated to mathematical statements. Chemistry and biology got along quite a time without mathematics.

Each science thus won a refined set of rules in the course of the time. Again and again contradictions emerged, which had to be fitted in.

It turned out that some events in the development of nature could just be described as a historical fact, but not as a physical law. Randomness was recognized as factor of influence for such historical events. So it is more or less random, when and where the earth was hit by meteorites and which influence such a meteorite impact on the development of the biological evolution took.

Since the term law of nature suggests safe knowledge, it should be used only critically.

Definition

A physical law, scientific law, or a law of nature is a scientific generalization based on empirical observations of physical behavior. They are typically conclusions based on the confirmation of hypotheses through repeated scientific experiments over many years, and which have become accepted universally within the scientific community. While there are no uncontroversial rules as to how or when a scientific hypothesis becomes a scientific law, scientific laws at their strongest are generally observations that have never had repeatable contradictions.

The production of a summary description of nature in the form of such laws is the fundamental aim of science. Laws of nature are distinct from the law, either religious or civil, and should not be confused with the concept of natural law.

Description

Several general properties of physical laws have been identified (see Davies (1992) and Feynman (1965) as noted, although each of the characterizations is not necessarily original to them). Physical laws are:

- true (a.k.a. valid). By definition, there have never been repeatable contradicting observations.

- universal. They appear to apply everywhere in the universe. (Davies)

- simple. They are typically expressed in terms of a single mathematical equation. (Davies)

- absolute. Nothing in the universe appears to affect them. (Davies)

- stable. Unchanged since first discovered (although they may have been shown to be approximations of more accurate laws—

- eternal. they appear unchanged since the beginning of the universe (according to observations). It is thus presumed that they will remain unchanged in the future. (Davies)

- omnipotent. Everything in the universe apparently must comply with them (according to observations). (Davies)

- generally conservative of quantity. (Feynman)

- often expressions of existing homogeneities (symmetries) of space and time. (Feynman)

- typically theoretically reversible in time (if non-quantum), although time itself is irreversible. (Feynman)

Often, those who understand the mathematics and concepts well enough to understand the essence of the physical laws also feel that they possess an inherent intellectual beauty. Many scientists state that they use intuition as a guide in developing hypotheses, since laws are reflection of symmetries and there is a connection between beauty and symmetry. However, this has not always been the case; Newton himself justified his belief in the asymmetry of the universe because his laws appeared to imply it.

Physical laws are distinguished from scientific theories by their simplicity. Scientific theories are generally more complex than laws; they have many component parts, and are more likely to be changed as the body of available experimental data and analysis develops. This is because a physical law is a summary observation of strictly empirical matters, whereas a theory is a model that accounts for the observation, explains it, relates it to other observations, and makes testable predictions based upon it. Simply stated, while a law notes that something happens, a theory explains why and how something happens, in terms of the more fundamental laws.

Examples

Some of the more famous laws of nature are found in Isaac Newton's theories of (now) classical mechanics, presented in his Principia Mathematica, and Albert Einstein's theory of relativity. Other examples of laws of nature include Boyle's law of gases, conservation laws, the four laws of thermodynamics, etc.

Laws as approximations

Some laws are low (or high) limits of others, more general laws (or as scientists say, of more fundamental laws). For example, Newtonian dynamics (which is based on Galilean transformations) is simply the low speed limit of laws of special relativity (simply because Galilean transformation follow from Lorentz transformation at the limit of low speed). Similar, the Newtonian gravitation law follows from general realtivity at the limit of low gravitational potential (compared to square of speed of light), and Coulomb's law follows from QED at large (compared to range of weak interactions) distances. In such cases we understandably use more simple laws-approximations instead of more accurate fundamental laws.

Those laws which are just mathematical definitions (say, fundamental law of mechanics - second Newton's law ), or uncertainty principle, or least action principle - are absolutely correct (simply by definition). Others which reflect symmetries found in Nature (say, identity of electrons or homogenuity of space and time) are constantly being checked experimentally to higher and higher degree of accuracy. The fact that they have never been seen repeatably violated does not preclude testing them at increased accuracy, which is one of main goals of science. It is always possible for them to be invalidated by repeatable, contradictory experimental evidence, should any be seen. However, fundamental changes to the laws are unlikely in the extreme, since this would imply a change to experimental facts they were derived from in the first place.

Well-established laws have indeed been invalidated in some special cases, but the new formulations created to explain the discrepancies can be said to generalize upon, rather than overthrow, the originals. That is, the invalidated laws have been found to be only close approximations (see above examples), to which other terms or factors must be added to cover previously unaccounted-for conditions, e.g., very large or very small scales of time or space, enormous speeds or masses, etc. Thus, rather than unchanging knowledge, physical laws are actually better viewed as a series of improving and more precise generalisations.

Origin of laws of nature

Some extremely important laws are simply definitions. For example, central law of mechanics F = dp/dt (Newton's second "law" of mechanics) is not a law at all but is a mathemetical definition of force (introduced first by Newton himself). The principle of least action (or principle of stationary action),Schroedinger equation, Heisenberg uncertainty principle, and a few other laws fall into this category.

Most of the other laws are mathematical consequenses of various mathematical symmetries (see Emmy Noether theorem as a proof of this). For example, conservation of energy is a consequence of the shift symmetry of time (no time moment is different from any other), while conservation of momentum is a consequence of the symmetry (homogeneity) of space (no place in space is different from any other). Indistinguishability of similar particles (say, electrons, or photons) results in the Dirac and Bose statistics which in turn results in the Pauli exclusion principle for fermions and in Bose condensation for bosons. Symmetry between time and space coordinate axis results in Lorentz transformations which in turn results in special relativity theory. Symmetry between inertial and gravitational mass results in general relativity, and so on.

So to large extent laws of nature are not laws of nature per se, but mathematical expressions of certain simplicities (symmetries) of space, time, etc.

The application of these laws to our needs has resulted in spectacular efficacy of science – its power to solve otherwise intractable problems, and made increasingly accurate predictions. This in turn resulted in design and implementation of variety of reliable transportation and communication means, in building more quality and affordable shelters, in creating variety of drugs, in finding new energy sources, in developing variety of entertainments, etc.

History, and religious influence

Compared to pre-modern accounts of causality, laws of nature fill the role played by divine causality on the one hand, and accounts such as Plato's theory of forms on the other.

In all accounts of causality, the idea that there are underlying regularities in nature dates to prehistoric times, since even the recognition of cause-and-effect relationships is an implicit recognition that there are laws of nature.

Progress in identifying laws per se, though, seems to have been hampered by belief in animism, and by the attribution of many effects that do not have readily identifiable causes—such as meteorological and astronomical phenomena— to the actions of various gods,spirits, supernatural beings, etc. Early attempts to formulate laws in material terms were made by ancient philosophers, including Aristotle, but suffered from lack of definitions, lack of experimenting, and hence had various misconceptions - such as the assumption that observed effects were due to intrinsic properties of objects, e.g. "heaviness", "lightness", "wetness", etc - which were results lacking accurate supporting experimental data.

The formal and precise formulation of what are today recognized as correct statements of the laws of nature did not begin until the 17th century in Europe, with the beginning of accurate experimentation and development of advanced form of mathematics (see scientific method).

Despite lay belief that laws of nature are somehow God(s) given), there is no scientific evidence of that - because most laws are either simply definitions or statements of identity (or symmetry), irrespective of its causes.

In essence, modern science aims at minimal speculation about metaphysics, and laws of nature are the result. The case for this method was perhaps most crucially made in the works of Francis Bacon.

Significance, and renown of discoverers

Because of the understanding they permit regarding the nature of our existence, and because of their above-mentioned power for problem-solving and prediction, the discoveries or defining (creation) of the new laws of nature are considered among the greatest intellectual achievements of humanity. Due to their subtlety, their discovery has typically required extraordinary powers of observation and insight, and their discoverers are typically considered among the best and brightest by others in their fields, and, notably in the cases of Newton , Einstein, Emmy Noether, in the general populace as well.

Other fields

Some mathematical theorems and axioms are referred to as laws because they provide logical foundation to empirical laws.

Examples of other observed phenomena often described as laws include the Titius-Bode law of planetary positions, Zipf's law of linguistics, Moore's law of technological growth. Many of these laws fall within the scope of uncomfortable science. Other laws are pragmatic and observational, such as the law of unintended consequences. By analogy, principles in other fields of study are sometimes loosely referred to as "laws". These include Occam's razor as a principle of philosophy and the Pareto principle of economics.

Not a law of nature

Kein Naturgesetz

Der folgende Text stammt von dem berühmten Philosophen Thomas Hobbes. Er deklariert zwei Regeln des menschlichen Zusammenlebens zum Naturgesetz. Nach Ansicht der meisten Naturwissenschaftler handelt es ich dabei nicht um Naturgesetze:

Wie im letzten Kapitel gezeigt worden ist, befindet sich der Mensch in dem Zustand des Krieges aller gegen alle. Jeder wird nur von seiner eigenen Vernunft geleitet und es gibt nichts - so man es nur in den Griff bekommt - was einem nicht dabei helfen könnte, sein Leben vor seinen Feinden zu schützen. So hat dann in einer solchen Lage jeder ein Recht auf alles, selbst auf das Leben seiner Mitmenschen. Und folglich kann es keine Sicherheit für den Menschen geben (er mag noch so stark oder klug sein), sich in der Zeit seines Lebens, die ihm die Natur im Allgemeinen schenkt, zu erfreuen, solange dieses natürliche Recht eines jeden auf alles besteht. Als eine Vorschrift oder allgemeine Regel der Vernunft hat daher zu gelten: Jeder Mensch suche Frieden, solange er hoffen kann, dieses Ziel zu erreichen, und nehme allen Nutzen und Vorteil eines Krieges wahr, wenn du zu keinem Frieden gelangen kannst. Die erste Hälfte dieser Regel ist das erste und wichtigste Naturgesetz, nämlich: Suche Frieden und bewahre ihn. Die zweite Hälfte besagt: Verteidige dich, ganz gleich auf welche Art, und schließt somit jegliches Naturrecht in sich. Auf dieses erste und grundlegende Naturgesetz, welches den Menschen befiehlt, nach Frieden zustreben, gründet sich das zweite: Zur Erhaltung des Friedens und zu ihrer eigenen Verteidigung sollen alle Menschen - sofern es ihre Mitmenschen auch sind -, bereit sein, ihrem Recht auf alles zu entsagen und sich mit dem Maße an Freiheit zu begnügen, das sie bei ihren Mitmenschen dulden...

(aus: Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, XIII, Kapitel, zitiert nach: Rowohlts Klassiker der Literatur und der Wissenschaft, Band 6, herausgegeben von Peter Cornelius Mayer-Tasch, Reinbek 1965, S. 102 f.)

Naturkonstanten

Die drei grundlegendsten Naturkonstanten sind nach heutiger Ansicht:

- die Gravitationskonstante G = 6,6742 x 10-11 m3 / ( kg * sek2 )

- die Lichtgeschwindigkeit c = 299.792.458 Meter pro Sekunde

- und das Plancksche_Wirkungsquantum h = 6,62607 * 10-34Joule mal Sekunde

Mit Ehrfurcht liest man als Nichtfachmann die Werte dieser Naturkonstanten. Man kann dann unter Physikern aber sofort eine lebhafte Diskussion herbeiführen, wenn man fragt, warum gerade diese 3 Konstanten so grundlegend sind und ob sie sich vielleicht auf eine noch grundlegendere einzelne Konstante oder auf die mathematischen Konstanten wie Pi oder die Eulersche Zahl e zurückführen lassen.

Fragen

Eine interessante Frage ist die, nach den einfachsten und wichtigsten Naturgesetzen. Auf welchen Fundamenten ruht das Gebäude der Naturgesetze ?

Eine weitere wichtige Frage ist die Abgrenzung des Begriffes Naturgesetz von historisch richtigen Aussagen, denen man aber eher keinen Rang als Naturgesetz zubilligen will.

Sind mathematische Sätze als Naturgesetze anzusehen oder nicht ? Die geometrische Aussage : Die Winkelsumme eines Dreiecks in der Ebene beträgt 180 Grad ist richtig. Ist das aber ein Naturgesetz ?

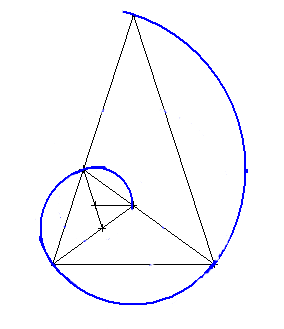

Abb.: Der Goldene Schnitt: Ein Naturgesetz ?

a-----------------------------a b-----------------bc----------c a = b + c a / b = b / c = 1,618033988....

Zitate

- Das Buch der Natur ist mit mathematischen Symbolen geschrieben. - Galileo Galilei

- Die Natur macht keine Sprünge, heißt es. Und die Kinder: Sind sie etwa keine Natur? - Gregor Brand

- Die Gesetze der Natur sind wunderbar, aber ihr Räderwerk zermalmt viele Insekten wie die Regierungen viele Menschen. - Antoine de Rivarol, Maximen und Reflexionen

- Jedes Naturgesetz, das sich dem Beobachter offenbart, lässt auf ein höheres, noch unerkanntes schließen. - Alexander von Humboldt

- Und wenn du noch so oft an ihre Türen klopfst, die Natur wird nie erschöpfend Auskunft geben. - Iwan S. Turgenjew, Aufzeichnungen eines Jägers

- Wir können die Natur nur dadurch beherrschen, daß wir uns ihren Gesetzen unterwerfen. - Francis Bacon

- Ein Naturgesetz folgt dem anderen, und der Wolf dem Schafe. - Aus Albanien

- Warum sollten die Naturgesetze an der menschlichen haut enden ? B.F.Skinner

References

- Barrow, John (1991). Theories of Everything: The Quest for Ultimate Explanations. (ISBN 0-449-90738-4)

- Davies, Paul (1992). The Mind of God (ISBN 0-671-79718-2)

- Feynman, Richard (1965). The Character of Physical Law (ISBN 0-679-60127-9)

- Hans Wehrli: Metaphysik - Chiralität als Grundprinzip der Physik, 2006, ISBN 3-033-00791-0

- Francis Bacon "Novum Organum"

- Die Struktur wissenschaftlicher Revolutionen.

- Thomas S. Kuhn:

- Suhrkamp Taschenbücher Wissenschaft Nr.25. 2., rev. u. erw. Aufl. Nachdr. 2001. 238 S.

- ISBN 3-518-27625-5, KNO-NR: 00 47 37 36 10.00 EUR - 18.70 sFr

- Kuhns Thema ist der Prozeß, mit dem wissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse erzielt werden. Fortschritt in der Wissenschaft - das ist seine These - vollzieht sich nicht durch kontinuierliche Veränderung, sondern durch revolutionäre Prozesse. Dabei beschreibt der Begriff der wissenschaftlichen Revolution den Vorgang, bei dem bestehende Erklärungsmodelle, an denen und mit denen die wissenschaftliche Welt bis dahin gearbeitet hat, abgelöst und durch andere ersetzt werden: es findet ein Paradigmenwechsel also ein Wechsel in den Anschauungen statt. So wurde beispielsweise in der Physik der Äther als Träger des Vakuums und der Kraftfelder abgeschafft.

- Was ist ein Naturgesetz?

- Schrödinger, Erwin

- Beiträge zum naturwissenschaftlichen Weltbild. Scientia Nova. 5. Aufl. 1997.

- ISBN 3-486-46275-X, KNO-NR: 01 61 96 05

- -OLDENBOURG- 19.80 EUR

- Was ist ein Naturgesetz?

- (engl. Originaltitel: What is a law of nature?, Cambidge University Press, 1985)

- von D. M. Armstrong

- Ein hervorragendes und anregendes ... Buch. Wenn es auch im Detail diskutierbar ist, so ist es doch klar, nachvollziehbar, präzise, fair gegenüber seinen Gegnern und voll von guten, originellen Argumenten. Alle kommenden Arbeiten über Naturgesetze werden von diesem Buch ausgehen.(D.H. Mellor in The Times Literary Supplement)

- Richard P. Feynman,The Character of Physical Law (1965), Penguin 1992.

- Philosophia naturalis:

- Archiv für Naturphilosophie und die philosophischen Grenzgebiete der exakten **Wissenschaften und Wissenschaftsgeschichte. Hrsg. v. Bernulf Kanitscheider, **Bernd-Olaf Küppers, C. U. Moulines u. a..

- Bd.37/2 Was sind und warum gelten Naturgesetze?.

- Hrsg. v. Peter Mittelstaedt u. Gerhard Vollmer. 2000. IV, S. 190-475. 23,5 cm.

- ISBN 3-465-03118-0, KNO-NR: 09 33 32 36

- -KLOSTERMANN- 45.00 EUR - 73.00 sFr

- Wie die Naturgesetze Wirklichkeit schaffen. Über Physik und Realität

- Genz, Henning: München: Hanser, 2002. 364 Seiten -

- Gibt es auch als rororo science Nr 61630

Zitat: Wir wollen es dabei belassen, daß die Realität der Welt uns insofern verborgen ist und wohl auch bleiben wird, als diese sich nicht durch Gesetze äußert, die auf unserer Ebene erkennbare Auswirkungen besitzen oder besitzen werden. Durch die Auswirkungen haben wir erkannt, daß erstens unsere Prinzipien nur unsere sind, also auf tieferen Ebenen nicht gelten, und daß zweitens auf den tieferen Ebenen kein gesetzloser Zustand herrscht, sondern einer, der Prinzipien unterliegt. Auf jeden Fall besitzen die Naturgesetze eine härtere und klarere Realität als die Objekte, von denen sie sprechen.

External links

- Baaquie, Belal E., "Laws of Physics : A Primer". Core Curriculum, National University of Singapore.

- Carroll, John W. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Francis, Erik Max, "The laws list". Physics. Alcyone Systems

- [1]

- Exact measurement of natural constants