Telescope Making

by the fine folks at The Skope Werks

A long time ago, when I was a kid living on a farm in Oregon, I wanted a telescope. I wanted a telescope because it was cool, because Jimmy had one, because I liked to look at the stars. Mostly I wanted a telescope to look around. I didn't want to admit it but I liked to look at the stars and the moon. I liked to watch birds and the way the snow melted off the mountains in the spring. Some things are just better seen in snippets of detail from a distance as a big picture.

Telescopes are expensive when you don't have any money, which was me most of the time. But telescopes have been around a long time, since 1608, and some books have been written on how to make one. I got one of those books for Christmas when I was 10. I still have that book.

One day when I was 46 years old, I had some extra money and some extra time. I was cleaning up in my room and I found my telescope book and I decided, “I'm going to make a TELESCOPE!”

I am not the sharpest tool in the drawer but I set out to learn how to make a telescope. What I found along the way, all the mistakes I made, all the neat tricks I learned, that is what I am going to share with you dear reader. You can make a telescope for around $25. You can make one for $50 that will knock your socks off and show you things you didn't know existed. I will show you how to make the telescope and how to use it and how to have some fun along the way. It won't take you 36 years like it did me, but it will take a few weeks, maybe a month or two. The process can get messy. It can get broken. It can make you walk around in the worst mood you have been in since when. But in the end you will have a telescope that people will look at and look through and say, “you didn't make this, you couldn't have made this.” Yeah I did, and that is the best part of all.

Lets make a telescope.

Telescope Making

Making a telescope requires some thought. In this book we will visit and revisit terms and ideas, always building on what we looked at the last time. Uncommon words and topics are listed at the bottom of the page with links to pages that explain them. You may also find links there that point to private web pages on various allied subjects. You should check out those links; they are worth looking at.

Basic Designs

To build a telescope we must have some idea of what a telescope is, how it works and how we will use it. The first project in this book is a Newtonian reflector made of scrounged parts. Other projects will follow as the book grows. However, all the telescopes that exist are based on two designs, the Refracting optical system and the Reflecting optical system. Some telescopes are a combination of both designs.

Refracting Telescopes

The very first telescopes were refracting telescopes. A refracting telescope is a series of lenses held in optical collimation that gather and focus light. The name comes from the action of the light as it moves through the lenses. The glass refracts or bends the light due to the properties of the glass. Because of this the light is broken up into the various colors that form white light.

The shape of the lens brings the light to focus, but because the glass has refracted the light, the image has false color around it. This is most noticeable on bright objects.

Simple refracting telescopes can be made with a magnifying lens of long focal length, (The Objective Lens), paired with one of short focal length, (The Eyepiece). A usable primary lens can be found in many types of equipment that use projection lenses and other optical components. Small inexpensive refracting telescopes can often be found at surplus and used merchandise stores very cheaply.

Reflecting Telescopes

The reflecting telescope is designed around mirrors. Because it does not transmit the light, but just bounces it in another direction, there is no refractive affect. No false color. The mirrors must be precise enough to accurately reflect and focus the light without introducing distortion. That is not as hard to do as it sounds. The first project, the Newtonian Reflector, will require mirrors, and we will make them. It is really very easy to do. Physics is on our side.

Links to new terms and topics for this page:

Collimation (english)

Collimation (english) Refraction (english)

Refraction (english) Refracting Telescope (english)

Refracting Telescope (english) Reflecting telescope (english)

Reflecting telescope (english)

Project 1: The Newtonian Reflector

The Newtonian Reflector Telescope is an extremely simple and efficient design. If you read the article at wikipedia (the link is below), you can see that there are some decisions that must be considered prior to starting construction of the telescope. Two questions that need to be answered right away are how will you use the telescope and where will you use the telescope. These two questions, and storage when not in use, will directly affect the design.

Thinking About Your Telescope

What Will You Do With Your Telescope? Most folks, me included, spent a lot of time dreaming about making the telescope without giving much thought to how it might be used. For instance, at the beginning I talked about looking at stars and planets. I also talked about looking at birds and retreating snow fields. The problem is, the basic Newtonian telescope makes everything look upside down. Looking at stars? This is not an issue. Looking at birds? We have a problem. Fortunately there are inverters you can buy for the telescope that will turn things right side up. A second issue with the Newtonian telescope is that it is by design quite powerful. This means you might be looking at bird feather detail, not the bird. Thirdly, the telescope is larger than a pair of binoculars and may require setup and maintenance. I don't want you to stress over this, but you need to consider, what will you do with the telescope?

Telescope Design

The telescope design is everything from the optics (in our case the mirrors) through the mounting of those optics. The type of tube assembly to use. The mounting of the mirrors in the tube. The type of mount for the tube and mounting the tube in that assembly.

So looking at the previous section, let's say you want to look at planets and stars in the sky. Longer focal length telescopes give bigger images. That is just the nature of the design. The longer the focal length, the bigger the image at focus. Bigger mirrors will gather more light, but two telescopes with different sized mirrors but having the same focal length will have the same size image at the focal point. Long telescopes are good telescopes and the mirrors are somewhat easier to make. The telescopes themselves are longer, more difficult to move around and store.

Shorter telescopes give a good image also. The image is a bit smaller but that is rarely an issue when looking through the eyepiece. The mirrors require a bit more work, a different technique, but they are as easy to make as the long ones. Shorter telescopes can be easier to move around, easier to store, easier to mount and setup.

There is no right answer here. The telescope you make should be one you are comfortable with and will use. I have made a lot of telescopes in the last few years. My first--I called it the Long Dog--was a truss design that took about five minutes and 10 bolts to set up. The truss poles were six feet long. The whole thing was heavy, long, hard to use without a ladder, and gave images that would take your breath away. I got one of my favorite comments while using that telescope. I showed a friend the planet Saturn. It was a perfect night, calm sky, dark, Saturn was high. He looked at the planet and said, "That is so amazing it doesn't look real." That is what we call resolution.

Regardless of the length and size of telescope you choose to make, you will find the information to build it here. I am going to do two mirrors and several mounting ideas for this, the first project of the book. I will grind and polish a shorter focal length mirror and a longer focal length mirror. Whatever you decide on I will cover it here and you will be successful with your first telescope.

Links to new terms and topics for this page:

Newtonian Telescope (english)

Newtonian Telescope (english)

The parts of the Telescope

Time to get into the nuts and theory of design. The following will have some basic math and some pictures to help. Hopefully you are thinking about your telescope and now you are going to see how those thoughts and decisions will affect the finished telescope.

The Optics

Having considered the physical size of the telescope and the use to which I want to put it, I can now begin to consider the optics. The amount of grinding, the depth of the curve on the front of the mirror, these are both directly affected by the choices I made while thinking about the telescope. There are relationships between the curve of the mirror front and the focal length. These have been given names by some of the first folks to make telescope mirrors and we just accept those names.

When we make a telescope mirror we use the front surface of the mirror to form the image and it is the front surface that gets all of our attention. The back may get quite beat up during this process. That is OK, as long as we don't crack it or put big chips in it.

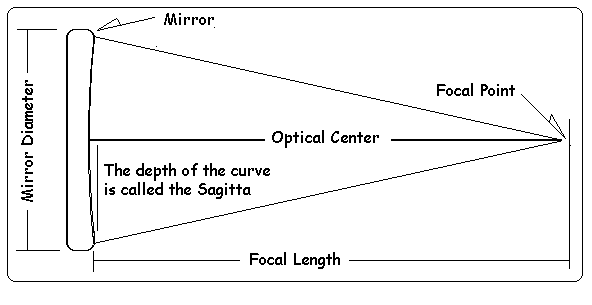

There is a curve to the front of a telescope mirror. That curve is called the Radius of Curvature, which is abbreviated ROC or even R. The front of the mirror is a smooth bowl shaped depression. Think about a ball, and if you have one handy get it to look at while you read this. The ball has some radius, the distance from the center of the ball (an imaginary point inside where you can't see it, but it is there) to the surface of the ball. That radius defines the ball's size and the curve of the surface. If we were to cut off a tiny slice of the ball, or press the surface of the ball into some soft material, say clay or moist dirt, we would form a shallow smooth bowl-shaped depression. It would be curved just like the front surface of a telescope mirror.

If we place a source of light ( a fancy way of saying put a light bulb or a flash light or something that makes light) at the center of the ball, and that ball was reflective inside, all of the light would reflect back to the light source, to the center. However, if we move the light source away from the center, the point of reflection, or focal point, will also move away from the center in the opposite direction. When the source of light gets really far away from the center of the ball, at infinity, the focal point ends up being about half way between the center of the ball and the surface of the ball. How far away is infinity? Well, figure at least 200 times the ROC.

The radius of the mirror or r, which just refers to how big around the mirror is (half its diameter), has nothing to do with the curve we put into the surface other than as a factor in the calculation of the depth of that curve. The bottom line here? The surface of the mirror has a uniform curvature. OK, maybe I belabored that point a bit too much.

Because the front of the telescope mirror has a bowl shaped curve to it, a telescope mirror is said to have Sagitta. This is the depth of the curve that is ground into the front of the mirror when compared with the edge of the mirror. It is deepest at the center of the mirror. There is a math formula to figure out how deep to go for a specific focal length.

I see ROC, and there is r, which we know to be the radius of the mirror. The formula reads, multiply the radius of the mirror times itself, then divide it by two times the Radius of Curvature. Huh? Well, we can measure the diameter of the mirror with a ruler or tape measure and divide it in half to get the radius of the mirror. If it is eight inches across, the radius is half of that or four inches. But how much is the ROC?

Well, you remember back a ways we talked about where the focal point moves to as the light source moves away from the center of the ball. When the light source is at infinity, or a long way away, the focal point is halfway between the center of the ball and the surface of the ball. Look at the drawing. So the focal length is one half the Radius of Curvature, one half the ROC. How long of a focal length did you want? How long of a telescope did you want? Lets say you wanted a three foot long telescope. The ROC is twice that length, or six feet. (If you have made a telescope before you are hemorrhaging right now because the length of the telescope has little to do with the focal length of the mirror. I'll clear it up before I'm done.)

I started asking, why am I figuring out the ROC when it is just another way of saying two times the focal length? Why not just use the focal length in the Sagitta formula? Since the formula uses two times the ROC, that is equal to four times the focal length. So, why not use this calculation?

Well, you can. For our purposes as amateurs we can use either and it will be good enough. By the way, I just used the first letters of focal length, fl, so I didn't have to write out the whole thing. I could have used just an f for focal length, just like r means radius.

So! let's figure out a Sagitta for an eight inch mirror with a focal length of forty eight inches.

| Sagitta calculation for a mirror eight inches in diameter and 48-inch focal length |

Not much is it? 0.08333 inches, (and those threes go on forever), is about one and one third 16ths of an inch. How much is that? About the thickness of a penny. A ream of paper is pretty close to 2 inches thick. There are 500 sheets in a ream. Since there are sixteen 16ths in an inch, there are thirty two 16ths in 2 inches. How many sheets of paper are in one 16th of an inch? About fifteen sheets. Since we are looking for one and one third 16ths that would be about 20 sheets of paper.

How accurate do you have to be? How close to a three foot telescope do you want? The focal length of the mirror will determine, to some extent, the length of the telescope tube. And for quick consideration you can assume the focal length of the mirror and the telescope tube are the same. BUT! In practice the telescope tube will possibly be about 25% longer. On a three foot (or thirty six inch) focal length, that means the tube could approach forty five inches in length

We have spent several paragraphs on the primary mirror and I have only shared the basics. Many good books and web pages document the making of the primary mirror. Look at the links at the end of the book. Now we need to consider the second half of the optics, the secondary mirror.

The Secondary Mirror

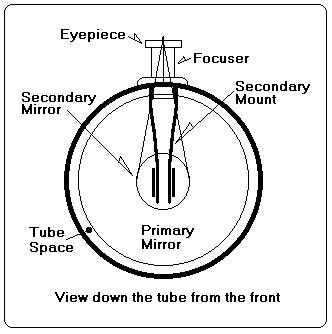

In the wikipedia page on Newtonian Telescopes we see that the telescope gathers and focuses the light, bouncing it back up the tube. Then the optical path is turned 90 degrees and the focus and eyepiece are on the side of the tube. This is accomplished with a flat mirror set at a 45 degree angle in the tube. Actually, you can use a roof prism in lieu of a flat mirror, if the prism is big enough. When the light beam (The old timers call it the pencil of light since it comes to a point) is fairly short, the beam is pretty big where it is intersected and bent. A prism that size is heavy, so most folks use a flat mirror.

How big the secondary should be, it's shape, and where it should be are functions of the basic measurements of the telescope, and the arrangement of the optics in the telescope tube. Aren't you glad that you have thought out your telescope so well? In the previous section we used an 8 inch mirror with a 48 inch focal length as an example for our calculations. I will continue to use that example in this section.

Before we can calculate the secondary size and location we need to look at the telescope tube a bit. How long should it be? How big in diameter? How far in will the primary mount?

OK, the tube needs to be bigger than the primary mirror; by how much? A good safe number is an inch on each side of the mirror. This works out to a tube that is two inches bigger in diameter than the primary mirror. So, for the 8 inch primary that is our example mirror, the tube would be 10 inches in diameter.

Tube length is determined by the focal length of the primary mirror, and the inset of the primary mirror and the mirror cell. Now in practice the tube could be the same length as the focal length of the primary mirror. This is very short and requires some compromise to make it work. Your average primary mirror and cell form a stack about 3 to 4 inches in height. Add that to the focal length and you would have a tube that is plenty long enough. Extra length, say 3 or four more inches, will give you some added front length which works to block stray local light from affecting the focuser. With that in mind, our example mirror has a focal length of 48 inches. Add 4 to that and we have a tube 52 inches in length. That takes care of the primary mirror and cell inset. Another 4 inches for light block and we have a tube 56 inches in length.

Our tube then falls within the lengths of 48 inches to 56 inches. It needs to be at least 10 inches in diameter.

So, how big is the secondary mirror? A common formula for figuring the size of the secondary is shown below.

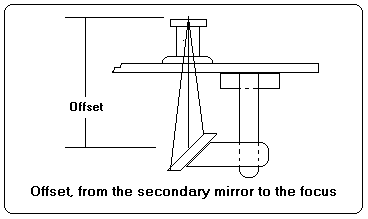

Multiply the diameter of the primary mirror by the focal offset and divide by the focal length of the primary mirror. This gives us a minimum minor axis. A second rule of thumb is, the secondary should not be any bigger than 20 percent of the pirmary mirror diameter. On an 8-inch mirror that is 1.6 inches, or about 1⅝ inches. Purists haggle over the numbers to the infinity. My opinion and experience are, it is better to have a secondary that is a bit too big, not a bit too small.

Lets look at that formula in operation. I used these variables:

- Os for the Offset,

- D for the Diameter of the primary mirror

- fl for focal length of the primary mirror

- d for the minor axis diameter of the secondary mirror

The formula yields a size of 1.33 inches or about 1⅜-inch minor axis. Remember, this is a minimum size. You could increase this by 25% and have a better secondary fit. 1.33 x 1.25 = 1.66 inches. Which just happens to be right at the 20% mark. Pretty cool huh? So the question now; what is offset? Oh yeah, I forgot that. A picture is worth a thousand words.

That's it! Using the decisions you made on the usage of the scope you should now be able to plan out a primary and a secondary mirror. You will be able to consider the tube size and you should have some idea on how this whole thing is starting to look. In the next section we are going to get down and dirty. We will abandon some of the purist things you have just learned so we can get a telescope built. HOWEVER! These considerations will shape even our scrounged telescope. What you have learned is the detail planning that you will put into your second telescope and every telescope you make after that first one. But you need to teach your hands how to grind and polish a mirror and that is best learned on simple inexpensive stuff.

The formulas are important enough that I have included them here on a graphic that will make a 3 x 5 card. Print it out!

| S = Sagitta |

| r = Radius of the primary mirror |

| fl = focal length of the primary mirror |

| r = minor radius of the secondary mirror |

| Os = Offset |

| D = Diameter of the primary mirror |

| fl = focal length of the primary mirror |

Links to new terms and topics for this page:

Vignetting (english)

Vignetting (english)

Making the Optics

The Mirror Materials

Lets talk about the materials needed to make a mirror. Strictly speaking what we want in a telescope mirror is a hard polishable material. One that we can shape with a simple mechanical process to the optical curve that we need. In the very earliest days of telescope making the material of choice was Speculum Metal. This was an alloy of Copper, Tin and Arsenic that was hard and nearly white. Somewhere along the way someone came up with a process to coat glass with a reflective material and the modern period of mirror making began. If you have a piece of metal that you think will polish out, I say try it. It was done before you can do it now,

Glass was originally basic soda lime glass. Sort of what we would call window glass today. Softer and easier to work than the metal, it could be polished out perfectly. However, glass expands and contracts with heat and this can make the transition period a nasty time to try and view the stars. The glass will move enough to mar the figure of the mirror, it's ability to direct all of the light to one point, and you are basically stuck until the mirror equalizes with the environment. This can take about an hour on small mirrors. In the search for glass that would not distort in this way many different blends of glass have been tried. Pyrex is harder and does not expand as much as the plate glass does. Fused Silica, and other exotic processes yield a glass like material that is harder and will yield a mirror that hardly changes at all. But! You can make a mirror out of any material that will take and hold the shape of the mirror's curve and many materials have been used. You can make a mirror out of various rocks. Cryptocrystalline Silica will work. I have a mirror made out a rock called Chert. It works fine. Volcanic glass or Obsidian has been used. The point is, if you can grind it and polish it you can make a mirror out of it.

For the first telescope mirror I am going to use a very common material. The ubiquitous Pyrex pie pan. Now, if you happen to have a piece of glass or something that you want to work with, use it. If you find a more traditional piece of glass while shopping for your pie pan, don't feel obligated to go with a pie pan. Use what you can get that is within your budget. Any piece of glass will work. Drink coasters, those big glass disks they put under decorative candles, glass serving platters. They are all glass, they are all round, they will all yield a mirror. Big glass ashtrays. You learn to look in the glass isle of the local thrift store with an open mind and three criteria; Roundish, smooth curve to the bottom, or flat and thick enough. If the bottom has a curve already the glass can be thinner than if you have to grind the curve in. And how much curve? And what is smooth?

I will answer the second question first. Take the glass item and hold it up against the front edge of the shelf. The shelf should be pretty straight but a little dimple won't hurt anything. There shouldn't be any big bumps or dips in the curved surface of the glass when compared to the straight edge of the shelf. Don't worry about any embossed words, they grind right off. The bottom, which is what we will work with, should be pretty smoothly curved. How deep is that curve? Your average coin, penny, nickel, dime etc. are all about 1/6th of an inch, more or less. Close enough for right now anyway. Hold the glass against the shelf edge and see of a nickel will slide through the gap. Will two pennies stacked on top of each other make it through? Use the middle of the curve when you test, that is the deepest part of the curve. Let’s say one penny will go through but not two pennies. That curve is just a bit less that 1/8th of an inch. Your average pie pan is about seven inches across the bottom, a little more or a little less, but about seven inches. So the mirror it will create is about seven inches in diameter. You have two parts of the saggitta formula, what is the focal length of that pie pan bottom?

Our saggita is about 1/8th of an inch, or .125 in decimal notation. The diameter of the mirror will be about seven inches, half that is the radius, r. Half of 7 is 3.5 in decimal notation. So we can express what we have and what we don't know as ..

So if we divide 3.5 squared by .125 we should get 4 times the focal length of the mirror....

hmmmm 3.5 X 3.5 = 12.25. Divide 12.25 by .125 and we get ... 98. So four times the focal length is 98 inches. 98 is pretty close to 100 inches, so the focal length is about 25 inches.

There are a lot of "abouts" in the above calculation because we don't know the exact depth of the curve. It is more than one penny deep but not two pennies deep. Two pennies is about 1/8th of an inch, depending on how old and worn the penny is. Did you get the penny though the middle or just to one side? Is there a hump in the middle? On and on and on the guessing goes and it isn't worth sweating about. Most all pie pans that have a smooth regular curve on the bottom have a curve about that deep. They all yield a mirror that is about seven inches in diameter, that will have a focal length of about 35 inches when they are finished. Trust me here, I've done a bunch of them. There are some tricks we can use to make a longer focal length if you want to. But right now we are getting our mirror material and we should stay on track. Maybe you see a big old ashtray that is about six inches across and pretty round with a generally smooth curve on the bottom. Testing with the penny at the edge of the shelf you find that a penny will just slide between the shelf edge and the glass...

Sagitta?? 1/16th of an inch, .0625 in decimal notation. Diameter is about 6 inches so radius is about 3 inches. So 3 X 3 is 9 inches, divided by .0625 is 144 inches which is four times the focal length. 144 divided by 4 is 36. So that ash tray will yield a mirror that is about 6 inches in diameter with a focal length of about 36 inches.

Just to be sure I knew what I was talking about I spent the last few weeks wandering around in various thrift stores, doing the things I talked about here. Yes, people will look at you strangely. Well just remember, Einstein was once considered a weird old man too. If they ask what you are doing tell them, or make up a good lie. I found five odd bits of glass that I bought for and average of $1.99 each. Though the two glass platters cost me $2.99 each. But! They will yield a nine and one half-inch mirror, which is a respectable mirror.

I got three pie pans, two glass platters and one white glass plate with an 8-inch bottom having a 1/8th inch deep curve. What is the focal length of that white plate?

Glass color does not matter. The glass can be any color, even rainbow. We will coat it when we are done, so who cares! I also found a 7-inch glass disk just a tad shy of one inch thick. I have no idea what it was for. It looks like some kind of fancy trivet or maybe a candle base. It is flat, so I will have to grind the curve in before I smooth it out. That is OK, it is plenty thick enough.

While you are out shopping buy at least one pie plate, we need it to make the tool. Go for cheap here, we are going to break it up into pieces so the cheaper the better. Now go find your mirror.

Other Parts You Need

There are other parts to the telescope and you should be looking for those parts while you look for your primary mirror. You will need a secondary mirror to bend the light at 90 degrees and bounce the image to the eyepiece. You will need a mount to hold the primary and the secondary mirror. You need a tube for the scope. A focuser assembly. A eyepiece and finally a mount for the telescope so you can point it where you want it. To use the telescope there are some other things like a finder and telescope cover that are handy to have, but the parts listed above are essential.

The secondary mirror is usually an oval shape. It is set at a 45 degree angle when it is mounted in the telescope tube and this makes the mirror look like a circle when viewed through the eyepiece or drawtube of the focuser. More important than the shape of the secondary is the flatness of the surface. It must be optically flat and that is very flat indeed. You can polish a secondary mirror to be flat and I will cover how to do that later on, but there are some sources of glass and mirrors that may answer the need without all the effort of making one. There are lots of cheap sources for front surface mirrors. Some old Polaroid cameras have a front surface mirror in them and can be found for pennies on the dollar at thrift shops. Old photocopy machines have very flat front surface mirrors in them. Even if you cannot find the mirror in an old photocopy machine, the flat glass on the top, as well as the flat glass on the top of old flat bed scanners, are a good source for the material to grind your own secondary mirror. Watch out for tempered glass, we cannot use tempered glass as it shatters when ground. If you get a pair of polarizing sunglasses, (sometimes there is a bin of these at the thrift store and you can borrow a pair to check a piece of glass), and hold the glass in question up to the light the sunglasses will reveal a pattern of dark spots in a piece of polarized glass. John Dobson always recommended the eyepieces from old binoculars for the eyepiece of a scope. Well, in that old binocular there are at least four prisms, all of which are optically good and may be big enough for your secondary mirror. Sometimes you can find just the body of an old binocular and the prisms will still be in there. Learn to share! Get a friend who also wants to make a telescope and go in halvies on some of these parts. Overhead projectors have mirrors in them, as do some slide projectors and movie projectors.

There are sources on the internet for old optical parts. I have listed a couple at the bottom of this section, but searching for optical parts, used optical parts or even surplus optical parts can yield a lot of good usable cheap stuff. You might also check local swap meets. See if there is a astronomy group in your area. Old amateurs telescope makers have lots of this stuff laying around. You get involved in this hobbie and then the stuff just appears. In a year or two you have to shovel out a load or you drown in the stuff. The best thing to do though is just keep your eyes open and your needs list at hand. You'll be surprised what you can find. Lastly, get to know your local glass shop owner. Cut off bits of thicker window glass can be ground flat and used for a secondary mirror. You can start with a simple rectangular mirror now and upgrade to a better shaped secondary later when you find one. It's your telescope, use it and rework it at will. In a way it is kind of like that first, bicycle or car or whatever. You get it and get it going and make it better over time.

We will make the mounts for the mirrors as well as the focuser assembly from scrap and scratch. Keep an eye out for popcycle sticks, tinkertoys, big roundish plastic or wood things like bucket or barrel lids. Little springs, maybe an inch or so long. Motorcycle clutch springs are great and are usually thrown away when they are replaced. Glue, tape, cardboard watch for cardboard. Everything from cereal boxes to refridgerator boxes. White plastic buckets like restaurants get food in. One or two of those are enough. Toilet paper tubes, paper towel tubes, the tubes from the inside of carpet or vinyl flooring rolls. Christmas paper roll tubes. Plastic plumbing pipes for sink drains. These are usually 1.5 inches or 1.25 inches inside diameter. The 1.25 inch ones are better but either will work. Old plastic vacume cleaner pipes. You can skip ahead to the chapters on tube design and focuser design to get some idea on how these parts will be used, but keep an eye open for them. Much of this is considered trash or recycling and to recycle it into a telescope is, I think, the highest purpose.

Links to new terms and topics for this page:

Speculum_metal (english)

Speculum_metal (english) Glass (english)

Glass (english) Chert (english)

Chert (english) Obsidian (english)

Obsidian (english) Pyrex (english)

Pyrex (english) Decimal_notation (english)

Decimal_notation (english) Einstein (english)

Einstein (english) John_Dobson (english)

John_Dobson (english)

Making the Tool

To make the mirror for a telescope we grind an optically perfect surface onto the material chosen to make the mirror. Simple, huh? It actually is pretty simple to do. The physics of the interaction between the mirror and the grinding tool assures us that one will develop a hole while the other develops a hump. Lets look at that for just a bit.

When grinding two surfaces of the same size, the surface that is on top will begin to hollow out or develop a bowl shape. The surface on the bottom will wear at the edge and develop a high center. It does this because of the stroke, the stroke length and the pressure we apply with our hands. The longer the stroke the deeper the hole. Shorter strokes flatten the curve. We will get into this a bit more later on but right now I want you notice that you are not just grinding the mirror, you are also grinding the tool. The action of the grind shapes both and this is exactly what we want to have happen. As the grind progresses mirror and tool become a perfect match. This interaction gives you one of several indicators as to how the grind is going. The sound of the grind, the feel of the interaction between mirror and tool, the bubble pattern that develops between the two surfaces. These are all indicators and you should be paying attention to them as you grind. The tool will become the base for the polishing lap. How well you shape the tool will affect how easy or hard it is to create the lap.

Tradition is to get two disks of glass the same diameter and grind. The top one becomes the mirror, the bottom one becomes the tool. That doesn't work with pie plates for a number of reasons. Fortunately the tool does not have to be an optical surface, it just needs to be a tool. The surface must be durable enough to survive the grind but must be soft enough to accept shaping by the grind. Tools are easy to make and that is what I recommend for the first mirror.

The simplest way to make a tool is to cast one out of some material. Plaster is cheap and will work to make a tool. You must be sure to seal it against water as the water will soften the plaster and cause it to fail. Concrete is more durable and as easy to work. Ceramic clay can be shaped and fired and used for a tool. You can use wood for the tool if you can match the curve of the glass pretty close. The reason that all of these various materials will work is because they will only form the base of the tool. Once the base is ready we glue the grinding surface to the base. The grinding surface is what gets shaped and this too can be made of many things.

Probably the easiest material to use for the grinding surface is broken glass. Ceramic tiles can be used as can washers, pennies, flattened marbles, decorative stones. Each will respond to the grind, each will grind in a particular way. Any of them are a valid choice.

My favorite tool is cast plaster or concrete with broken glass glued on for the grinding surface. That is the one I am going to discuss in the greatest detail but it is not the only way to make a tool. Your finished tool should match the curve of the pie plate pretty closely and should allow you to attach a grinding surface. It should be roughly the same size as the pie plate but a bit smaller is not an issue. Bigger will flatten the curve and increase the focal length. Substantially smaller, say half the diameter, will work but will require you to be very vigilant while grinding.

BUT! you do not have to make a tool. A ring is a section of any sphere larger that the ring. You can prove this to yourself by putting a ring against a larger sphere. The open end of a can, the mouth of a jar, the end of a pipe, these are all rings. Get a ring and hold it against a ball, a light bulb, the inside of the pie plate. You will find that the ring sits easily against the sphere. The reason I bring this up is that you can use a ring for your tool. At least in the coarser stages. So you could do a lot of the initial grinding with an old soup can, and that is a very valid thing to do. You will still need a larger tool for later but to get started you could use a ring.

So! if you are buying a pie plate to use for the mirror and if you decide to make a tool right now, get two and break one up for glass for the tool. You need a tool base, cast or shaped, carved or whatever and some glue to attach the grinding surface onto the base. I like 5 minute or 15 minute epoxy glue. The cost is reasonable and it will glue just about anything to anything.

Time to make the tool.

Making the Primary Mirror

Making the Secondary Mirror

The Telescope Parts

The Primary Mirror Cell

The Secondary Mirror Mount

The secondary mirror mount must hold the secondary mirror at the proper position in the tube and in the optical train. It must allow for minor adjustments of both of these positions and retain the final position without slipping. The mount is actually made of two parts, a mirror mount and a tube position mount. There are just a few considerations to think about ..

- Telescope tube size and shape,

- Secondary mirror size and weight,

- Material available,

- What you want to try and do.

I will start with the mirror mount.

The mirror must be held without tension so that the surface is not distorted, which would impact the image. Hard adhesive products contract as they cure and squeeze the glass, which in turn distorts the surface. Mechanical attachments, clips, rings, etc. must allow the mirror to float, because the differing rates of expansion of the different materials can squeeze or bind the glass. When you decide what mirror mount to use you should also consider how that mount will be attached to the tube position part of the assembly and how it will be adjusted to get proper collimation of the optical train.

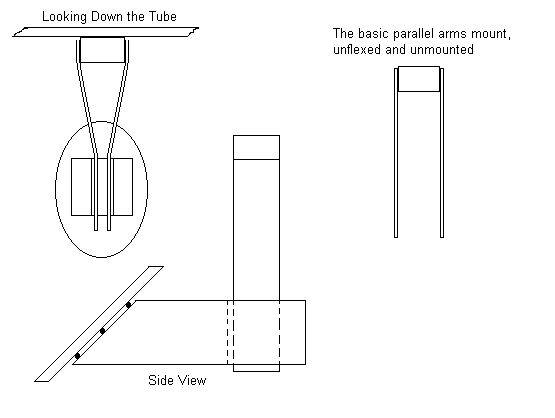

One of the oldest secondary mirror mounts is a simple mechanical mount. A short piece of tubing, a bit bigger in it's diameter than the minor axis of the secondary, is shaped by cutting one end at a 45 degree angle. Small L shaped clips are made and screwed or glued to the outside of the tube to hold the mirror in. The mirror is placed in the tube and cotton balls are loosly packed in behind it to hold it against the clips. The tube is then capped on the open end to hold the cotton balls in. See the drawing below ..

The idea here is that the tube takes all of the abuse of mounting and the mirror just floats inside the tube. The mirror is given it's basic orientation, (held at the proper angle), by cutting the end of the tube at 45 degrees and holding the mirror at that end with cotton balls. The mirror and the tube have about the same cross sectional area in the light path so additional obstruction is minimal.

This is a very good mount although it can be a bit difficult to make if you are short on tools. The tubing used can be plastic or metal or what have you, since you use a tube that is a little oversized and it really doesn't squeeze the mirror. You could make one of these out of a toilet paper tube pretty easily and it would function well. The clips could be of thin wood, (popcycle sticks), and could be glued on. The 45 degree angle on the front end should be as accurate as you can get it, but the optical alignment is accomplished with the tube position part of the mount and an angle that is a bit off is not a big deal. This mount is very good for the large secondary mirrors found in larger scopes.

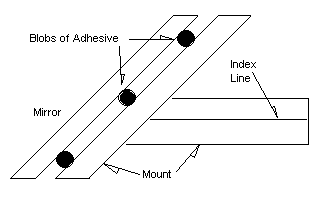

Another mount is made from a simple piece of wood or plastic or even metal. Take a dowel, or even a square or rectangular piece of material, that has ends smaller than the secondary mirror, and cut one end at a 45 degree angle. Now you can glue the mirror to the 45 degree face and you are done. Remember, I said hard adhesives will squeeze the glass as they cure so use a soft adhesive to attach the mirror. Silicon rubber, also called room temperature vulcanizing rubber, RTV for short, will hold the mirror but will not squeeze it as it cures. It also resists temperature changes so expansion or contraction are not a factor. It is a spongy material and will buffer the mirror from shocks and changes in the mount. You should use three small blobs to form the bond, not one big smooshed out blob in the middle. Use some toothpicks or small wood skewers to hold the mirror away from the mount so the glass and the mount are not in direct contact but are held together by the rubber.

Another adheasive you can use for this mount is double sided foam core tape. Get the thickest core you can get. I use this stuff eveywhere on the telescope to mount things, so a roll is a handy thing to have. You must make sure the mount material is very smooth on the cut end, so sand it off very smooth and coat it with layer of nail polish. Now just cut a single piece of tape, put it in the middle of the mirror and stick it on the end of the mount. The foam core provides the same sort of buffering stand off that we got with air and rubber and it is much easier to use.

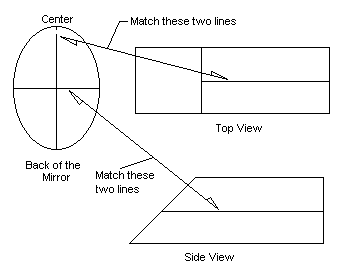

The danger in an adhesive based mount is not getting the mirror glued on squarely. The mirror must have it's minor axis perpendicular to the eyepiece for the minimum amount light obstruction. The simplest way to make sure it is properly lined up on the mount is to make some index marks on the mirror and the mount prior to gluing.

Get a sharp pencil and a ruler. Lay the secondary mirror face down on a piece of paper. Eyeball in the center, at the edge, of each end of the major axis. Get as close as you can but don't lose sleep over it. Make a little mark there with the pencil. Draw the diameter line for the major axis of the mirror, on the back of the mirror, using the two marks you made to orient the ruler. Go edge to edge. Now measure the major axis and divide it in half. Make a mark at the center of the major axis line and use the ruler to draw the diameter line for minor axis through that mark. Look at the drawing below. Get as close as you can and try to make the intersection of the lines at the middle of the mirror perpendicular to each other. Now take the piece of material you are using for a mount and draw a straight line one each side of the wood, as close the the middle of the side as you can. When you glue or tape the secondary to the mount, line up the lines on the mirror with the lines on the mount and you will be close enough.

These simple adhesive mounts will work well for smaller mirrors, the kinds of mirrors we will be using to make a pie pan telescope. Larger mirrors require a better mount and some form of mechanical mount would be best for those mirrors. There is a hybrid of these two forms that can be used for big mirrors.

Make an oval that matches the shape of your secondary mirror. Glue and screw that oval to the mount face, or weld it on if you are using metal. The oval should be made of good solid material. You should line it up just as you lined up the secondary in the above proceedure using the index lines. Now glue your secondary mirror to the oval using several small blobs of rubber or several pieces of tape. The mirror is well attached to the oval by the adhesive and the oval is mechanically attached to the mount assembly. You could also add a couple of small clips to the oval to help support the secondary mirror. Remember, the mount should not pinch or squeeze the mirror.

The Tube Position Mount

Now that the secondary mirror mount has been made or chosen, we need to work out placing it in the telescope tube. The secondary mirror should be mounted in the very middle of the tube to catch the focused image from the primary mirror and turn it towards the eyepiece and focuser. This process is decided more by measuring than anything, but there are some tricks we can use and there are many ways to position the secondary in the tube.

The first step is to measure the telescope tube diameter inside and outside. You can do the math and size the mount accordingly, but I like to draw a full size diagram and work from that. I take a piece of paper at least three or four inches bigger than the outside tube diameter. Draw lines across the paper from corner to corner using a straight edge. Where the lines intersect is the middle of the paper. Now I use a compass to draw a circle as big as the inside diameter of the tube, or a square if I am using a square tube. Now I can play with various ideas for mounting the secondary mirror in the tube. I can get real measurements and understand what I am going to be working on. Lets talk about some mounts.

The simplest tube mount is a single arm holding the secondary mirror at the right place in the tube. The arm is usually attached to the tube near the focuser hole or on the opposite side. This overcomes one distortion from gravity. If you mounted it to the side wall the arm could flex downward from gravity and make it hard to collimate the telescope.

Single arms are quick and elegant but they have a fatal flaw. They vibrate. That one arm with the weight of the secondary mirror at the end is rather like a pendulum and bumping the tube will make it vibrate for a while. If you use a thicker material and one that dampens movement, for instance a soft wood, you can minimize the vibration, but it will always be there. My telescope, "The Long Dog", had a single arm secondary mirror mount. It could be irritating but I did a lot of viewing with that telescope and I never swapped it out for something else.

Attaching the single arm to the secondary mirror mount can also be a challenge. If you use a piece of all thread metal rod you could bore a hole through the mount and through the tube wall and mount and center the secondary with nuts. That is why I used a single arm on "The Long Dog" as it gave me an infinit adjustment to place the secondary in the tube. Final collimation was accomplished by bending the threaded rod to position the secondary mirror. If you want to glue the arm on you need to be sure the mirror is in exactly the right place and will stay there while the glue dries.

A variation of the single arm is a design using thin parallel strips, closely mounted, and flexed together to form the single arm. This is basically a triangular truss and cancels all vibration. Collimation is achieved by moving the secondary mount on the truss. The friction of the material holds the alignment, or you can glue it up and fix the position pemanently. See the drawing below for details. You can make this assembly out of popcycle sticks, clothes pins or just thin scraps of wood. It could also be made from stiff plastic. This is the mount I use in my pie pan telescopes. It is also in my rock scope.

Really the only consideration is that the material used be flexable enough to not break when put into flexation by the secondary mirror mount. You should cut out the slot on the mirror mount prior to mounting the mirror on it. The slot should only be as wide as three or four pieces of the strip material you are using. There is no need to go wider at the top than 3/4 of an inch. A shorter set of arms would be better served by an even narrower top end, say 1/2 inch or so. The best thing to do is hold the assembly in your fingers and squeeze the ends of the strips to see how much tension there is and adjust the separation accordingly. You want enough tension to hold the secondary in place.

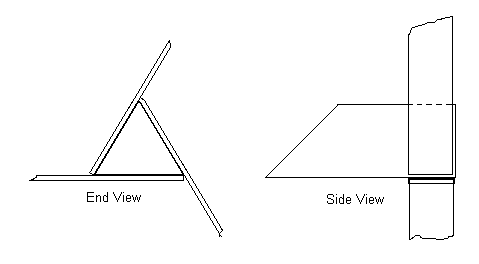

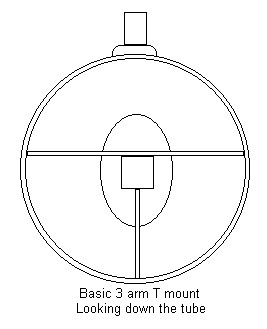

Three arm mounts are an old and reliable standard. The arms are cut to the length necessary to hold the secondary in the middle of the tube. They are then mounted equidistant around the secondary mirror mount so that by their very length they center the mirror in the telescope tube.

John Dobson has used this design forever it seems. Once he has the assembly put together he puts it in the telescope tube, collimates the scope and then glues it in place. He recommends and I agree that the arms should be wide and thin with the thin edge placed towards the tube opening, not round or square. This gives a better strength to the tube mount.

You can do this mount quite easily in wood. Make the mirror mount out of a piece of wood cut to the shape of an equilateral triangle. Think of a long prism. Now cut the 45 degree end for the mirror to mount on. Make the arms and glue and screw or nail them to the end opposit where the mirror will attach. Make sure they are perpendicular to the mirror mount. I cut the arms long and size them for length by centering the assembly on my drawing and marking the arms there. Once it is assembled and the glue has dried attach the secondary mirror and put the assembly in the telescope tube. John Dobson does this mount using a dowell. He cuts a groove in the side of the dowell at 120 degree intervals and then glues the arm into place in the groove.

A variation on the three arm is a single arm that goes all the way across the telescope tube and a second short arm that runs from the mirror mount to the wall of the tube. These are a great design as they are simple to do. They are also good for square mirror mounts.

You can add another arm and do a four arm mount. These are very stable and work well in round or square tubes The more arms you use the more complex the mounting becomes. But! It all comes down to the same batch of considerations.

- Telescope tube size and shape,

- Secondary mirror size and weight,

- Material available,

- What you want to try and do.

Make a decision based on the above considerations. Make a complete mirror mount first, including arms and then attach the secondary mirror. Finally, mount it in the telescope tube.

The Telescope Tube

The Focuser Assembly

The Telescope Mount

The Altitude or Vertical Bearings

The Azimuth or Horizontal Bearings

The Bearing Box

The Ground Board

The Legs

External Links

- The Surplus Shed, Optical Parts

- Astromart Telescope Making Page

- American Science and Surplus, Optical Parts

Further reading

- "Build your own telescope" shows how to set up an extremely low-cost demonstration of how telescopes work.

- The Cookbook Camera (CCD "Cookbook Camera" Project) was a great resource in 1996 for people who wanted to add a CCD to their telescope. Is "Wikibooks: Telescope Making" the best place to bring it up-to-date?

- adapting a low-cost web camera to a telescope

- adapting a low-cost web camera to a 35 mm film camera lens to make a telescope

- "The Trackball telescope"; "The Trackball telescope" describes yet another style of telescope mount that uses a sphere resting against a driven axle to track the stars.

- "Mel Bartels Mirror Making Page" One of the most respected and quoted amateur mirror and telescope makers.

- "Telescope Makers Web Ring Home Page" This is the home page where you can list your web site and show off your creation;This is the list of websites in the ring.

- "The Amateur Telescope Makers list server" You can join the list or just read the postings and the archives. A huge source of information.

- "The ATM Site: Resources and Techniques for Amateur Telescope Makers" Great ATM sites have come and gone but this site has preserved some of the best. Lots of articles to read.

Template:DDC

Template:LOC

Template:Shelf

Template:Alphabetical